by

Demetris

I. Loizos, B.A., M.A./M.Phil, D.HA

History

Professor

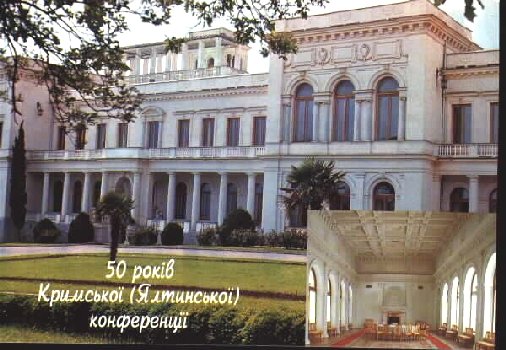

Yalta or Jalta is a city

located on the Crimean peninsula, nowadays in southern Ukraine. In 1928 it had a

population of about 30,000 and it was the center of the health resorts in the

Black Sea. However, when the Germans evacuated the area during the Second World

War, they caused damages to all the buildings and, therefore, in 1945 it was a

ruined city with roofless houses.[1]

This was the place that was chosen by the Big Three (F. Roosevelt, W. Churchill

and J. Stalin) as a meeting point in early 1945. Two Palaces from the tsarist

era were to offer hospitality to the three delegations. The plenary sessions of

the meeting were held every afternoon at the Livadia Palace, while the meetings

of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs as well as the military talks took place in

the Yusupov Palace in the mornings.[2]

Yalta or Jalta is a city

located on the Crimean peninsula, nowadays in southern Ukraine. In 1928 it had a

population of about 30,000 and it was the center of the health resorts in the

Black Sea. However, when the Germans evacuated the area during the Second World

War, they caused damages to all the buildings and, therefore, in 1945 it was a

ruined city with roofless houses.[1]

This was the place that was chosen by the Big Three (F. Roosevelt, W. Churchill

and J. Stalin) as a meeting point in early 1945. Two Palaces from the tsarist

era were to offer hospitality to the three delegations. The plenary sessions of

the meeting were held every afternoon at the Livadia Palace, while the meetings

of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs as well as the military talks took place in

the Yusupov Palace in the mornings.[2]

One of the focal points of discussion in Yalta was the Polish issue that

consisted of two major questions. The first one was the border line on both the

west and the east side of Poland and the second question was who was going to

govern the country.[3]

Concerning the Polish frontiers, the Russians aimed at the annexation of part of

the eastern territories of Poland which, in fact, were part of Russia before the

Russo-Polish war of 1920-1921. In 1921 the Treaty of Riga set the Polish

frontier 150 miles east of the Curzon line[4]

and a considerable number of Russians found themselves under Polish

administration. It was also true, however, that about one million Poles lived to

the east of the Riga frontier and therefore an ethnologically precise settlement

of the border was unrealistic.[5]

On the other hand, the problem of the Polish government was difficult as

well. In early 1945 there were two Polish governments. One of them was in exile

in London and it was referred to as the London Poles or London Government; the

other one was in Lublin (Poland) and it was referred to as the Lublin Committee

or the Lublin Government. The London Government was composed of the members of

the Polish Government who had fled the country at the beginning of World War II

while the Lublin Government consisted of young Poles who had remained in the

country during the war and belonged to the Left. In January 1945, the Lublin

Committee, being pro-Soviet, declared itself the Provisional Government of

Poland and it was immediately recognized by the USSR.[6]

Stalin justified this action of recognition in the following

words:

I think that Poland cannot be left without a government. Accordingly, the

Soviet Government has agreed to recognize the Provisional Polish Government

[...] I hope that events will show that our recognition of the Polish Government

in Lublin is in keeping with the interests of the common cause of the Allies and

that it will help accelerate the defeat of Germany.[7]

Stalin had already expressed his views clearly on this issue in a letter

to Roosevelt:

We cannot tolerate a situation in

which terrorists, instigated by Polish emigres

[non-communist elements who had left Poland after the beginning of the war]

assassinate Red Army soldiers and officers in Poland, wage a criminal struggle

against the Soviet forces engaged in liberating Poland and directly aid our

enemies, with whom they are virtually in league. [...] It should be borne in

mind that the Soviet Union, more than any other Power, has a stake in

strengthening a pro-Ally and democratic Poland [...] because the Polish problem

is inseparable from that of the security of the Soviet Union. To this I should

add that the Red Army's success in fighting the Germans in Poland largely

depends on a tranquil and reliable rear in Poland, and the Polish National

Committee [Lublin Poles] is fully cognisant of this circumstance, whereas the

emigre

Government [London Poles] and its underground agents by their acts of terror

threaten civil war [...][8]

Stalin rushed to recognize the Lublin Government in Poland because it was

loyal to the communists; he needed stability and tranquility in the rear of the

Red Army when the final offensive against Germany began in mid-January 1945.

Also, in this way, the London Government (anticommunist) would not have been

able to take over in Poland when the war would come to an end, although it was

the legal Polish Government. Furthermore, Stalin was aware of how much the Poles

disliked the Russians when they recalled the Soviet foreign policy before the

war. The Poles remembered well the Soviet policy of partition that had been

followed after a secret agreement between the USSR and Germany in 1939

(Ribendrop-Molotov Pact). After all, the whole history of Russo-Polish relations

is a history of mutual mistrust and national hatred. Therefore, Stalin had to

secure the support of the Polish Government in order to prevent any action of

the Poles against the Soviet army. Stalin would also like the idea of using in

the future Poland as a buffer state between the Soviet Union and the West: a

tsarist policy that had been followed after the 18th

century.

Both Roosevelt and Churchill expressed their disappointment with Stalin's

action and sent messages to him saying that the Polish question should be

discussed in detail at the Crimean conference.[9]

Churchill was much more distressed because he had tried to prevent Russian

influence in Poland using the London Government. A meeting was arranged between

Stalin and Mikolajczyk (head of the London Poles) in 1944 to solve their

differences. The London Government, however, did not want to accept the Curzon

line although this solution was supported by all three —Roosevelt, Stalin and

Churchill. When Mikolajczyk resigned and was replaced by Arciszewski, the new

London Government in exile had clearly become anti-Soviet.[10]

Churchill and Roosevelt, therefore, arrived in Yalta facing, on the one

hand, the fait accompli of the Polish

Provisional Government supported and recognized by the USSR and, on the other

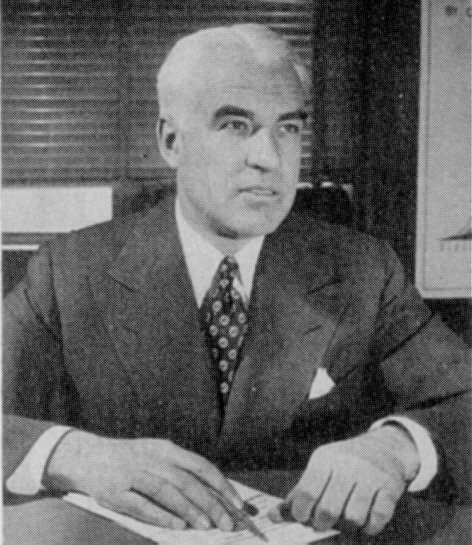

hand, the London Government that was irreconcilable in its views. The Secretary

of State, Edward Stettinius,  had already prepared a

memorandum of suggested action items for the President. In the case of Poland

the US favored the Curzon line in the east with the town of Lwow remaining in

Poland and a transfer of German territory limited to East Prussia (a small

coasted salient of Pomerania) and Upper Silesia (Map 1). The

USA also supported the formation of a new representative government that would

hold free elections when conditions permitted. Inclusion of Mikolajczyk in a

provisional government was considered to be important but the Lublin government

was not going to be recognized in its present form.[11]

had already prepared a

memorandum of suggested action items for the President. In the case of Poland

the US favored the Curzon line in the east with the town of Lwow remaining in

Poland and a transfer of German territory limited to East Prussia (a small

coasted salient of Pomerania) and Upper Silesia (Map 1). The

USA also supported the formation of a new representative government that would

hold free elections when conditions permitted. Inclusion of Mikolajczyk in a

provisional government was considered to be important but the Lublin government

was not going to be recognized in its present form.[11]

In this case, the Americans did not follow the policy of just diplomacy

at it refers to the nationalities. Although the Curzon line was not the best

solution for Poland and did not compensate the country for what it had suffered

during the war, it would appease the Russians and clear their grievances related

to the greater Poland of the interwar period. At the same time with Lwow

remaining Polish there would be no common border between Czechoslovakia and the

USSR and the latter would be far away from Hungary and Central Europe. The

western allies wanted as little Russian influence in this part of Europe as

possible. As far as the western Polish frontier was concerned, the Americans

offered Poland territory inhabited mainly by Germans and including East Prussia.

The inclusion of East Prussia would solve the irregularities that had been

observed with Wilson's policy of self-determination of populations, according to

which Germany was cut into two pieces because of the Polish Corridor to Danzig.

Last but not least, free elections were considered essential so that an imposed

government composed by communists would be avoided.

Although, therefore, the two first days of the Conference were devoted to

the discussion of the German problem or to informative meetings, on 6 February

1945 the discussion turned to Poland. President Roosevelt opened the discussion

on Poland by saying that he believed Americans were in favor of the Curzon line

and looked forward for a representative government in Poland that would be

composed of the leaders of the five political parties.[12]

Churchill confirmed that the British government was in favor of the Curzon line

(Lwow though remaining in the USSR) because Britain believed that a "strong, free and independent Poland was much

more important than particular territorial boundaries." Churchill claimed

that it was because he trusted the declarations of Stalin about the sovereignty

and independence of Poland that he placed the frontier issue second, meaning

they could be discussed later on.[13]

The British Prime Minister said that the Polish Government in London was

recognized by his country. Although he himself had had no contact with it, he

felt that Mikolajczyk, Gralski and Pouner (members of the London Government)

were all honest men. Churchill also suggested the creation of a government for

Poland to hold elections.[14]

Stalin began his speech by saying that the Polish question was for the

Soviet Union an issue of both honor and security because both countries had

long-lived disputes between themselves and a strong Poland would not become

again "a corridor for attack on

Russia."[15]

Stalin was very much against the Curzon line because it left Bialystok (or

Belostok) and the Bialystoc region to Poland (Map 1).[16]

It seems that the Russians would feel more secure with a Russo-Polish border

along the two rivers west of Bialystok. Stalin was also very critical of

Churchill's proposal to create a Polish government in Yalta and said that "a Polish government could be set up only

with the participation and consent of the Poles." He claimed that the London

Government dropped Mikolajczyk because it did not want to come to an agreement

with the Lublin Government. Moreover, he said that the latter refused to hear of

any unity with the government in exile. Stalin was upset because he wanted

tranquility in the Red Army's rear and he had information that some underground

forces had killed 212 Soviet soldiers. Therefore, according to him, the Warsaw

Government turned out to be useful and the London Government and its agents in

Poland, harmful in this war against the Germans. Stalin concluded that he would

support the government that would give peace in the rear of the Russian army.[17]

Roosevelt said nothing.

That same night Roosevelt, after he consulted with Churchill, sent a

letter to Stalin, part of which read as follows:

In so far as the Polish Government

is concerned, I am greatly disturbed that the three Great Powers do not have a

meeting of mind about the political set up in Poland. It seems to me that it

puts all of us in a bad light throughout the world to have you recognizing one

government while we and the British are recognizing another in London

[...]

[...] I would like to develop your proposal a little and suggest that we

invite here to Yalta at once Mr Bierut and Mr Osubka Morawski from the Lublin

Government and also two or three from the following list of Poles [representing

...] the other elements of the Polish people. [...] We could jointly agree with

them on a provisional government in Poland which should no doubt include some

Polish leaders from abroad such as Mr Mikolajczyk, Mr Gralski, and Mr Romer

[...][18]

Most

probably, the Americans foresaw the dangers that the open question of the

formation of a representative Polish government had created and rushed to make

their ideas clear before the next meeting. It seems though that the opportunity

to exercise pressure on Stalin was missed when Roosevelt remained silent in the

last meeting during the day.

The next day (7 February 1945) Stalin stated that he had received the

President's letter but he was not sure if there would be enough time for both

the representatives of the Lublin Poles and those of the London Government to

come to the Crimea.[19]

In this way Stalin postponed any real action of the delegations at the

Conference to solve the problem of the Polish government immediately. Moreover,

he suggested that the American legation

listened to the proposals Molotov had worked out. Molotov proposed that

(1) the Curzon line would be the eastern frontier of Poland; (2) the Polish

western frontier would run from the town of Stettin (Polish) to the south along

the rivers Oder and West Neisse (Map 1 and Map 2); (3)

some democratic leaders from Polish emigre

circles would be added to the provisional Government; (4) the enlarged

Provisional Government would be recognized by the Allies; and (5) would call the

Poles to polls as soon as possible.[20]

Stalin tried to prove his good intentions by accepting the Curzon line and

compensating Poland with German territory in the west. He also accepted the idea

of "emigres"

Poles, as he called them, in the future government. Stalin might have thought

that he had nothing to loose by promising the allies what they had more or less

actually demanded, since the Red Army had virtually occupied the whole of Poland

and was now approaching Berlin (Map 3: Front line

8 February 1945).

Both Roosevelt and Churchill were embarrassed with the word "emigre"

that was used and Churchill proposed to change it to "Poles temporarily abroad,"

to which Stalin agreed. Churchill was also not satisfied with the western Polish

boundaries and particularly concerning the area west of the river Oder (Map 1). Those

territories, continued Churchill, were heavily populated by Germans and the

Russian proposal would involve a movement of German population. "It would be a great pity to stuff the Polish

goose so full of German food that it died of indigestion," concluded the

British Prime Minister. But Stalin assured him that the Soviet Army would leave

no Germans in this area.[21]

Meanwhile, Stettinius passed to the President the following written

warning: "Have we the authority to deal

with a boundary question of this kind, giving a guarantee?" When Churchill

began to speak, Roosevelt wrote on a piece of paper: "Now we are in for 1/2 hour of it."[22]

Stettinius wanted to warn Roosevelt that they might be involved in a frontier

question that could be discussed again after the end of the war under new

circumstances. It seems that Roosevelt was thinking that the primary aim of the

Conference was to show the world that there was agreement of decisions among the

Big Three.

In the morning of 8 February Roosevelt sent a letter to Stalin regarding

the Soviet proposal for Poland. The American delegation was not in favor of the

extension of the western Polish frontier up to western Neisse river. Moreover,

the Americans proposed that Polish leaders from both governments be invited to

the Crimea to form a "Polish Government of National Unity." A Presidential

Committee would also be formed and would undertake the formation of the

government of National Unity composed of representatives from the Warsaw

Government, from elements inside Poland, and from Poles abroad. The immediate

action of that government would be the organization of elections. The new Polish

Government of National Unity would be recognized by all three Governments of the

Crimean Conference as the Provisional Government of Poland.[23]

It took the Americans another whole night to realize that the western Neisse

frontier line was unacceptable.

Molotov answered the American proposal for a government of National Unity

by stating that the Soviet Union felt that it would be better to enlarge the

existing Warsaw Government because it enjoyed great prestige and popularity in

Poland. On the other hand, Mikolajczyk, Grabski, and Witos had not been

connected with the events of the liberation of the country. He was against the

creation of a Presidential Committee but in favor of the enlargement of the

existed National Council. On the question of the frontier, Molotov was sure that

the Polish will was in accordance with the Soviet proposal.[24]

When Molotov talked about the enlargement, Stettinius sent the following written

message to the President: "Mr President:

Not to enlarge Lublin but to form a new Gov. of some kind."[25]

The Americans feared that Stalin's friends would be the majority in the enlarged

government.

Churchill

intervened at this point saying that a lack of agreement on the recognition of

one Polish Government only would stamp the meeting "with the seal of failure."

He stated that the British were informed that the Warsaw Government was not

accepted by the majority of the Poles. Moreover, he said that he did not agree

with the London Government's actions and he proposed free general elections in

Poland with universal suffrage and free candidatures. Britain, he continued,

would then recognize the government regardless of the attitude of the Polish

Government in London.[26]

It is worth noting that that same day the British delegation circulated its own

proposals. They proposed that the western frontier of Poland included the free

city of Danzig, the region of East Prussia, west and south of Konigsberg,

the administrative district of Oppelm in Silesia, and the lands desired by

Poland east of the Oder line (Map 1). An

exchange of the Polish and German populations of the above area was suggested as

well as the establishment of a Polish government representing all democratic

elements of the country. Elections would be held as soon as possible.[27]

Churchill

intervened at this point saying that a lack of agreement on the recognition of

one Polish Government only would stamp the meeting "with the seal of failure."

He stated that the British were informed that the Warsaw Government was not

accepted by the majority of the Poles. Moreover, he said that he did not agree

with the London Government's actions and he proposed free general elections in

Poland with universal suffrage and free candidatures. Britain, he continued,

would then recognize the government regardless of the attitude of the Polish

Government in London.[26]

It is worth noting that that same day the British delegation circulated its own

proposals. They proposed that the western frontier of Poland included the free

city of Danzig, the region of East Prussia, west and south of Konigsberg,

the administrative district of Oppelm in Silesia, and the lands desired by

Poland east of the Oder line (Map 1). An

exchange of the Polish and German populations of the above area was suggested as

well as the establishment of a Polish government representing all democratic

elements of the country. Elections would be held as soon as possible.[27]

On 9 February at noon the Foreign Ministers Stettinius, Molotov, and Eden

met at the Livadia Palace to discuss the Polish question. Stettinius dropped the

American proposal on the creation of a Presidential Committee. However, he

suggested the following formula:

[...] the present Polish

Provisional Government be recognized into a fully representative government

based on all democratic forces in Poland abroad, to be termed "The Provisional

Government of National Unity" [...] This "Government of National Unity would be

pledged to the holding of free and unfetter selections as soon as practicable on

the basis of universal suffrage and secret ballot in which all democratic

parties would have the right to participate and to put forward

candidates."

When a "Provisional Government of National Unity" is satisfactorily

formed, the three Governments will then proceed to accord its

recognition.[28]

Molotov

asked to study the Russian translation first and Eden pointed out that he was

against an action in favor of the Lublin Government because it would involve

complicated issues of recognition in respect to the London Government. He also

insisted on the formation of a new government in Poland.[29]

In the plenary meeting of the same day Molotov asked for the substitution

of the first sentence of Stettinius draft with the

following:

The Present Provisional Government

of Poland should be recognized on a wider democratic basis with the inclusion of

democratic leaders from Poland itself and from those living abroad, and in this

connection this government would be called the National Provisional Government

of Poland.[30]

Molotov

also asked for the addition of the words "non-Fascist and anti-Fascist" before

the words "democratic parties" in the last sentence of the paragraph.[31]

After a half-hour intermission Roosevelt said that he proposed the change of the

first words of Molotov's suggestion. Instead of the "Provisional Government" he

proposed the use of the words "The Government now operating in Poland". He also

expressed the view that there should be an inclusion for the desire of free

elections that was expected by the six million Poles in the United States.[32]

Stalin agreed with the amendment of the President.[33]

On the same day at the meeting of the Foreign Ministers Molotov disagreed

on the last sentence proposed by Stettinius which read as

follows:

The Three governments recognizing

their responsibility as a result of the present agreement for the future right

of the Polish people freely to choose the government and institutions under

which they are to live, will receive reports on this subject from their

ambassadors in Warsaw.[34]

The

question on the inclusion of the above sentence was left to the Big Three

Meeting next day.

On 10 February 1945 at the meeting of the Foreign Ministers Stettinius

stated that the Polish question had given serious study and that the American

delegation was prepared to withdraw the last sentence which Molotov had objected

to.[35]

The new formula therefore included the following points: (1) the Polish

Provisional Government would be recognized after the inclusion of democratic

leaders from Poland and from Poles abroad; (2) the new Provisional Polish

Government of National Unity would organize elections; (3) after the formation

of the new government, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain would

establish diplomatic relations with Poland and the ambassadors would report to

the respective governments about the situation in the country.[36]

Churchill disagreed on the formula because it did not make any mention of

frontiers. He believed that the British War Cabinet would not accept the line of

the western Neisse.[37]

At this point Stettinius informed the President that he was told by Eden that he

had received a "bad" cable from the Cabinet which expressed its fear that the

British delegation was going too far. Meanwhile Harry Hopkins of the American

mission scribbled to Roosevelt the following note:

Mr President:-

I think you should make clear to Stalin that you support the eastern

boundaries but that only a general statement be put in communiqué saying we are

considering essential boundary changes. Might be well to refer exact statement

to foreign ministers.

Harry[38]

Roosevelt

told the plenary session that he believed that the Polish Government should be

consulted before any statement was made in regard to the western frontier.

Stalin and Churchill proposed that the same action should be taken for the

eastern frontier too. Molotov, therefore, suggested that he should form a last

sentence on the Polish formula.[39]

Almost at the end of the meeting of that day, President Roosevelt said that he

had to propose some small amendments concerning the frontiers of Poland and the

respective formula.[40]

The changes were accepted by the conference and the final draft read as

follows:

The Three Heads of Government

[instead of "the three powers"] consider that the eastern frontier of Poland

should follow the Curzon line with digressions from it in some regions of five

to eight kilometres in favor of Poland. It is recognized that Poland must

receive substantial accession of territory in the North and West. They feel

[instead of "agree"] that the opinion of the new Polish Provisional Government

of National Unity should be sought in due course on the extent of these

accessions and the final delimitation of the Western frontier of Poland should

thereafter await the Peace Conference.[41]

The text was finally approved by all parts and Roosevelt announced that

he had to leave by 3 p.m. the next day and a committee was appointed to prepare

the Conference communiqué. The communiqué on Poland noted the enlargement of the

Polish Provisional Government which would hold "free and unfettered" elections;

the recognition of the Curzon line as the eastern frontier of Poland; and that

the western frontier would be settled at the Peace Conference.[42]

By the end of the Yalta Conference, Poland and almost all of eastern

Europe was controlled by the Red Army. Stettinius claimed that "as a result of this military situation, it

was not a question of what Great Britain and the United States would permit

Russia to do in Poland, but what the two countries could persuade the Soviet

Union to accept."[43]

Problems and dissatisfaction with the agreements at the Yalta Conference were

expressed a few months after the end of the meeting. On 1 April 1945 Churchill

wrote to Stalin that he was embarrassed because the "new" and "recognized"

Polish Government had not been established yet, because the "Soviet or Lublin

Government" vetoed any invitation to Poles abroad that they did not approve. He

also mentioned the fact that Molotov withdrew his offer to allow observers or

missions to enter Poland.[44]

Stalin answered to Churchill's complaints by complaints. He claimed that the

"Polish question had indeed reached an impasse," because of the attitude of the

British and American ambassadors in Moscow. According to Stalin they ignored the

Polish Provisional Government and they wanted to invite Polish leaders from

abroad who did not recognize the decisions of Yalta.[45]

Apart from the British, however, Poles in America were also disturbed in 1945 by

the agreement on the boundaries. Congressmen of Polish origin[46]

as well as Polish-American organizations denounced the Curzon line as being

another partition of Poland. The Curzon line after all was the old

Ribendrop-Molotov line that had divided Poland between Russia and Germany.

Congressman O'Konski declared that "without a free Poland there can be no free

Europe or a free world. The fate of Poland will determine whether the war has

been won or lost."[47]

The American Secretary of State, E. Stettinius, provided a balance sheet at the

end of his book on the Yalta Conference. His opinion is that the agreement on

Poland was more or less a concession by Stalin to both Roosevelt and Churchill.

"It was not exactly what we wanted, but,

on the other hand, it was not exactly what the Soviet Union wanted,"[48]concluded

Stettinius. (Map

4)

Stettinius had definitely

the impression that in the case of Poland the Americans and the British had not

allowed Stalin a free hand in Poland. The close study of the documents shows,

though, that all three sides were afraid of one another. All three had agreed

that they wanted the creation of a territorially unified Poland. They agreed on

the eastern frontier along the Curzon line. In this way the Russians received

what they had been asking for the last forty years. The western allies wanted to

show Stalin that they would satisfy the territorial appetite of Russia in that

area and at the same time Stalin would help them with Germany and most important

with the final phase of the war against Japan.

Stettinius had definitely

the impression that in the case of Poland the Americans and the British had not

allowed Stalin a free hand in Poland. The close study of the documents shows,

though, that all three sides were afraid of one another. All three had agreed

that they wanted the creation of a territorially unified Poland. They agreed on

the eastern frontier along the Curzon line. In this way the Russians received

what they had been asking for the last forty years. The western allies wanted to

show Stalin that they would satisfy the territorial appetite of Russia in that

area and at the same time Stalin would help them with Germany and most important

with the final phase of the war against Japan.

For a moment, the western frontier seemed to have created new problems.

Stalin at the beginning insisted on the Polish acquisition of an area

(Neisse-Oder) heavily populated by Germans, in an attempt to appease the Lublin

Government. In the future that regime would declare that although the Poles lost

to the Russians an area that historically was part of the old 17th century

Jaggelonian Empire (Poland-Lithuania) in the east, they were compensated with

Eastern Prussia and the area up to the Neisse river. Finally Stalin agreed to

the reconsideration of the western frontier issue. This move was interpreted by

Stettinius as a retreat but it seems that Stalin was not quite sure on what

points he could exercise pressure on the western allies. On the question of the

Polish government it appears that Stalin was more interested in a regime that

would be friendly to the Russians rather than to a purely communist government

in Poland. That is why at the end he yielded to the formation of a government

recognized by all three governments. Of course, he tried to postpone any real

action on this matter for latter on when the Russians would have complete

control of Poland and might not need the allies to finish that war. All in all,

Stalin was assured in Yalta that the Americans and the British would more or

less agree to his plans concerning Poland. Stalin should have left Yalta

satisfied with what he had achieved on the Polish issue.

The British, on the other hand, had to face the London Government which

had showed no cooperation and finally denounced the Yalta agreements. Churchill

had to go back to Britain and assure the British cabinet that the Big Three had

solved the Polish question in the best possible way. Stalin had accepted the

participation of "Poles from abroad" in the Provisional Government of Poland; an

independent Poland would be created in accordance with the British policy

concerning this country; Stalin had promised free elections. Churchill was not

so naive to be convinced of what the Russian bear had told them in Yalta. Yet,

the western allied forces needed the Russians desperately in early 1945. In

early February the western allies were just recovering from the German attack.

They needed the Russians to exercise more pressure on the eastern front or even

siege Berlin (Map 3) to

force the Germans to relieve pressure on the western front. Churchill,

therefore, left Yalta satisfied that at least Stalin would not abandon his

allies now that he was winning his part of the war and that at least legally he

had bound himself to a free and independent Poland. The British knew that they

could trust the Americans more than they could believe in Stalin's

promises.

It seems that the Americans reacted last in the Conference at Yalta. Was

it because Roosevelt had just won his third Presidential elections in the autumn

of 1944 and was very tired with a failing health? Well, it appears that his

advisers were alert and made suggestion during the actual meeting. The

President, though, needed time to think and discuss probably over and over the

various possibilities usually during the night. Then the Americans reacted to

what was usually a talk of Churchill and Stalin during the day. Was Roosevelt to

blame for the fate of Poland? FDR had just won the elections and was definitely

not concerned for the time being with the Americans of Polish origin in the USA.

He was very much interested, though, in the course of the war. The Russians were

very close to Berlin and the Americans had to rush to meet them there but that

would not be the end of the war. The Americans thought that they needed the help

of Stalin in the war against a still very powerful Japan (as they thought),

which could last for months or even years after the defeat of Germany. The

President could now go back to Washington hoping that Stalin would respect the

alliance after the end of the war in Europe.

In the final analysis all three leaders left the Crimea confident that at

least they had not broken off the alliance, an act that Hitler would appreciate

and hope reading over and over how Frederick the Great escaped from complete

destruction in the 18th century. The Prussian Emperor was saved at the last

crucial moment before the collapse of his army when the coalition against him

was dissolved. Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin left the Crimea assured that each

one had won that round in the game of international politics. Stalin had

acquired the eastern part of Poland and an acceptance of the presence of

communism in the future government of Poland. Churchill had secured the

participation of Poles from abroad in the future government and that would, at

least, be appreciated in London. Roosevelt had assured the entry of the USSR in

the war in the Pacific and had not allowed Stalin a free hand in

Poland.

History has proven that all three were deceived in Yalta by one another.

The use of the atomic bomb ended the war faster than they expected and Russian

assistance was not that an important factor. Britain could not afford to play

the role of a world power any more and passed the baton to the USA, which felt

that had to protect the principles of the republic all over the world and

therefore could not trust the untrustworthy: the Russians. Stalin, on the other

hand, saw that he could not trust the Americans who had the power now to destroy

any part of the world. He had to protect the Soviet Union by allowing the

descent of an "iron curtain" between eastern Europe and the West. President

Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill and Marshal Stalin used Yalta in the Crimea

as a summer resort in the cold winter days of February

1945.

*

* *

NOTES