Issue O023 of 1 September 2002

The Murals of the Roman Villas

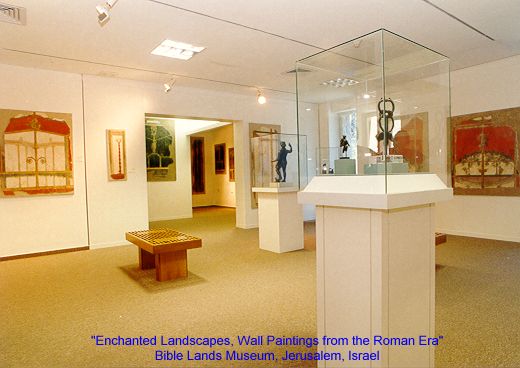

Enchanted Landscapes

(An Exhibition at the Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem, Israel)

By

Norman A. Rubin

Journalist, Indep. Scholar

The paintings that decorated the walls of palaces, town and country homes, tombs, public buildings and temples in Rome and Campania from the Second Century BC to the First Century AD is of unique importance. They have intrinsic value as works of art, and are practically the only surviving examples of the famous lost paintings of classical antiquity. These works of art provide a vivid reflection of daily life in ancient times; through them we gain insight into the aesthetic experience of Rome and are able to see which themes were considered important in Roman society. Classical myths, elements from the theater, genre scenes, still lifes and sacred landscapes - all are depicted on the wall paintings.

The paintings that decorated the walls of palaces, town and country homes, tombs, public buildings and temples in Rome and Campania from the Second Century BC to the First Century AD is of unique importance. They have intrinsic value as works of art, and are practically the only surviving examples of the famous lost paintings of classical antiquity. These works of art provide a vivid reflection of daily life in ancient times; through them we gain insight into the aesthetic experience of Rome and are able to see which themes were considered important in Roman society. Classical myths, elements from the theater, genre scenes, still lifes and sacred landscapes - all are depicted on the wall paintings.

The few paintings that survived in Rome, Ostia and their surroundings also reflect contemporary developments, following the same evolution as the Campania examples. In their range of subjects and styles, the works from the two regions illustrate the evolution of the art form of paramount importance; the interior decoration of the Roman villa.

Our knowledge of the greatness and tremendous variety of these works is due to a tragic event. On the 24 August, 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius erupted, burying the cities of Campania province under layers of ashes, mud and lava. It was this disaster that preserved most of the examples of wall paintings known to us today. The superb mural decorations of the villas, of Pompeii. Herculaneum, Stabiae, Boscoreale, Boscotrecase, and Oplontis remained covered until regular excavations began in the eighteenth century, continuing to this day.

Although many paintings have been preserved in situ in various Italian cities, other examples from these regions are today exhibited in museums around the world. The ruins of Herculaneum were first discovered in 1594, and Pompeii began to be excavated in a serious way after 1748. Excavations have been in progress for over two centuries now, but it was not until the more painstaking, extensive archaeological work of the present century that care was taken to leave the paintings where they were. In the past, many of them were detached from their original walls ending up in a variety of collections. (1)

MURAL DECORATION AND STYLE

The art historian Augustus Mau in his book "Pompeii, its Life and Art" (Berlin 1882) classified Roman wall paintings according to four consecu tive styles, based on form and technique. (The chronological sequence of these styles has often been challenged, but recent research confirms the basic validity of Mau's system.)

The First (or 'Incrustion') Style is the oldest and simplest found at Pompeii. It dates from the beginning of the second century BC and consists of plain, painted stucco panels that imitate the facing of real marble walls and reflect its structural divisions. The panels are modeled in relief, with color applied to suggest the use of different types of stone.

The Second Style emerged in Rome early in the first century BC. It creates the illusion of space by introducing purely pictorial imitations or architectonic forms; large panels depict architecture, landscapes, and figures. The upper part of the painted panel is opened to suggest a glimpse of an outside world and creates an illusion of depth.

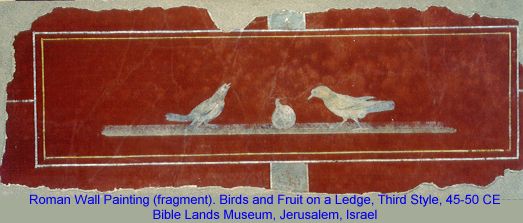

The Third Style (14 BC - 62 AD) aims chiefly at ornamental effect. It rejects illusionism, instead employing fanciful architecture with slender columns and candelarbra that divide the space of the wall. The designs are now characterized by a minute attention to detail and a more accentuated use of color. The grand-scale panels, elaborately ornamented are painted on white and vivid red backgrounds, containing motifs from the figurative and ornamental world. (2)

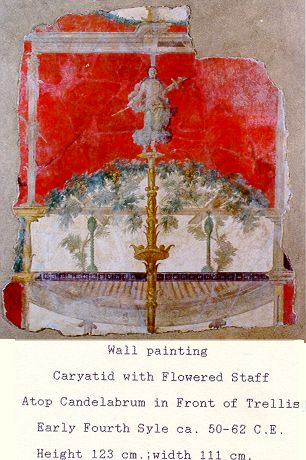

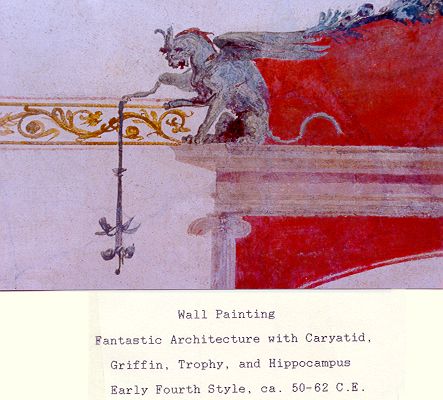

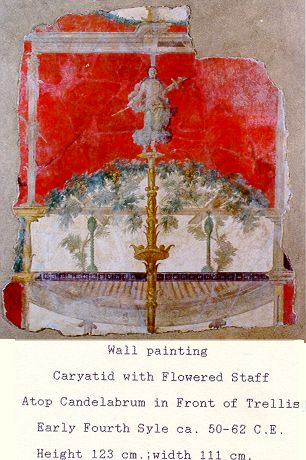

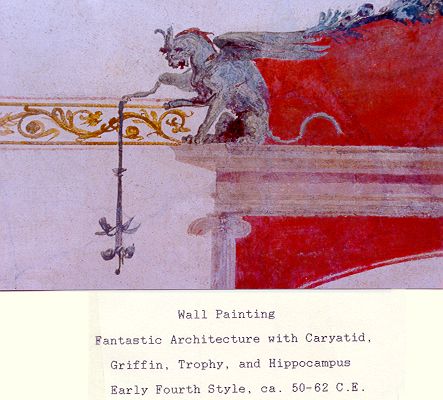

The Fourth Style reached Pompeii before the earthquake of 62 AD and continued outside the city until the end of the first century. It takes up the architectural and perspective models of the Second Style, now enlivened with fantastic motifs of an elective and baroque nature. Narrow openings full of air and light appear between the various wide ornamental panels and floating figures, and are painted in an impressionistic technique emphasizing the play of light and shadow.

MOTIFS AND DESIGNS

MOTIFS AND DESIGNS

The different objects - garlands, caryatids, and fantastic mythological creatures, flying and standing figures ornament the architectonic views of the painted villa wall panels. Bronze vessels resting on top of partitions or entablatures were used to enliven the architectural framework.

The architectural elements themselves are connected or entwined by garlands and tendrils. The garlands embellished with a variety of flowers and fruit, which abound in great quantity in the countryside and in gardens attest to the fertility of the area. (The Romans at banquets and on numerous festive holidays wore garlands; they are often shown in reliefs and mosaics adorning shrines.)

The fantastic creatures that ornament the architectural design come from the world of Greek mythology - the griffin, a fabled monster having the head wings of an eagle and the body of a lion - related to Apollo, a creature believed to guard hoards of gold in distant lands: the sphinx, a mythical creature having the head and breast of a woman, the body of a lion and the wings of an eagle, which was regarded by the Greeks and Romans of a creature of arcane wisdom: the hippocampus, a sea horse with two forefeet, and a body ending in a tale of a dolphin (3) which was related to the Neptune, god of the sea. The mythological symbolism of these creatures seems to be of no interest to the artist who used them only for decorative purposes. The Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius criticized abusively these outlandish ornamental wall decorations, "Such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been."

For the Romans and Pompeians who devoted a good portion of their time to religious observance in their homes, life was bound up with religious cults, whether private or public. The most revered god of the local communities was Apollo (4); the deity and his sister Diana, frequently appeared as decorative motifs in the important rooms.

The figures, both flying and standing, painted with touches of shadow, show the play of drapery, contributing to the work's three-dimensional effect. The theatrical effects are enhanced with caryatids standing lightly on upper trays of candelabrum, heads tilted upwards, and with a staff crowned with vine leaves and ivy. The upper parts of the bodies are nude with the lower part draped with a long white and green garment dappled with touches of shadow.

THE TECHNIQUE OF ROMAN WALL PAINTING

THE TECHNIQUE OF ROMAN WALL PAINTING

Information concerning the technical processes involved in Roman wall painting is provided, not only by the surviving examples from ancient cities, but also by contemporary literary sources. According to the Vitruvius, "six coats were needed to prepare a wall for painting - three of sand motar and three more of fine-grained plaster with marble dust...." (This number of layers was reduced, and by the late period, only two were used.) The Roman historian Pliny, in his writings, meticulously described the kinds of colors and pigments used, the composition of the layers of plaster, and the way in which the painting surface was finally polished to produce its characteristic sheen.

The pigments (a mixture of minerals such as hematite, galena, chalk, malachite, etc. with animal or vegetable fat) were ground up, carefully mixed and kept in little clay pots. The colors applied to the wall paintings are mixed - green, yellow, purple lines over a yellow-orange background to suggest a three-dimensional architectonic composition; shades of red, green and black backgrounds to enhance the theatrical effect; columns painted in beige and pale pink so that the differences in shading of the colors suggest depth; trellises of green grape vines and purple grapes arranged in a convex shape; dark and light green foliage roofs of bushes and fruit; garlands with light and dark leaves and yellow, orange and purple fruit; figures wearing costumes of pink, blue and green, the body highlighted with vibrant touches of pink-orange brush strokes; mythical creatures are in a variety of colors to effect their different functions in the paintings. The wall-painter's chief tool was, of course, his brush, which was made of pig's bristles.

Usually color was applied using the 'fresco' technique while the plaster was still damp; occasionally, however, 'tempera' (paint mixed with a bonding agent, and applied to the to the dry surface), was used for details and for colors, such as from light blue to some tones of green, that could not be applied to a damp wall. Liquid wax might also be added for certain colors, such as vermilion, or for the walls exposed to the open air, as well as paintings on wood, marble or ivory. (5)

The finished painting was burnished using a metal trowel, marble or glass cylinder, or special polishing stone, and buffed with a clean cloth.

CONCLUSION

The wall paintings of the Roman villas are almost as they were when they were created all those centuries ago. They were part of a life-style, important expressions of Roman culture and a reflection of the values of the period. Today they provide an incomparable source of information concerning the culture, the tastes and concerns of its people, and the subjects that most interested the Roman world. In these paintings, antiquity comes alive. (6)

|

THE ROMAN VILLA

The typical Roman villa was designed to face inwards, towards its center, with small bedrooms (the Cubicala) and at least two open halls (the Alae) surrounding an (the Atrium), main or central room, open to the sky at the center and usually having a pool for the collection of rain water. The rooms tended to be small, with inadequate artificial lighting and heating: Natural lighting was mainly through the opening (the Compluvium) centered in the 'Atrium'.

Other chambers such as the service room and servants quarters, were situated behind the bedrooms. On the far side of the Atrium, far from the entrance, was a large elaborate room (the Tablinum) used for receiving visitors and for formal occasions. Alongside was the dining room (the Triclinium), furnished with a couch extending along three sides of a table, for reclining after meals. The hearth was set in a prominent corner and dedicated by paintings and statuary to the domestic dieties, the 'Penates', the gods of the food cupboard (Penus) and to 'Vesta', the goddess of 'hearth fire'.

At the rear of the house, a courtyard of decorative plants was enclosed in a colonnade that complemented the architecture. Every house had an altar dedicated to one or more of the many Roman gods, which was usually placed in a prominent place in the courtyard. Ceremonial utensils (found in excavations) attested to the rites and devotion to the gods.

The rooms were beautifully decorated - covered with wall paintings, stucco ornaments, and floor mosaics. Almost every room in the house, whether large or small, was embellished with magnificent decorations. It bore witness to the prosperity and exquisite taste of their owners.

|

NOTES

1) Many of the Roman villas in the area of Pompeii discovered before World War I were reburied whether deliberately by their excavators, or naturally by the eruptions of Mount Vesuvius in 1906.

2) The wall paintings influenced King Herod in his trips to Rome that he decided to bring Italian artists back to Palestine - artists who produced the first examples of this type of decorative art, which was applied to the wall panels at Herod's palace at Jericho. Thereafter, this style of wall paintings became part of the monumental art in the provinces of Syro-Palestine.

3) Dolphins were a common decorative theme in Roman wall painting. They were sacred to Venus, the goddess of love; they were usually depicted in light shades of green, drawing the chariots of sea god Neptune and his wife Amphitrite, or frolicking around them in the bluish-white waves.

4) The Greek connection - In succession all the great gods of Ancient Greece was introduced into Roman religion. Apollo sprang in all his novelty into the midst of the Roman gods and won himself a position of great eminence.

5) In some instances, the pigments were so costly that the artist did not pay them for, but by the patron who commissioned him.

6) Information for this article has been derived from an exhibition at the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem, Israel (guest curator, Dr. Silvia Rozenberg, curator of Classical Archaeology, Israel Museum, Jerusalem) and from Enchanted Landscapes by Dr. Silvia Rozenberg (R. Sirkus Publishers Ltd. Israel). On mythological issues you may consult the Encyclopedia of World Mythology, forwarded by Rex Warner, Octopus Books Ltd, London.

Back to Cover

Back to Cover

The paintings that decorated the walls of palaces, town and country homes, tombs, public buildings and temples in Rome and Campania from the Second Century BC to the First Century AD is of unique importance. They have intrinsic value as works of art, and are practically the only surviving examples of the famous lost paintings of classical antiquity. These works of art provide a vivid reflection of daily life in ancient times; through them we gain insight into the aesthetic experience of Rome and are able to see which themes were considered important in Roman society. Classical myths, elements from the theater, genre scenes, still lifes and sacred landscapes - all are depicted on the wall paintings.

The paintings that decorated the walls of palaces, town and country homes, tombs, public buildings and temples in Rome and Campania from the Second Century BC to the First Century AD is of unique importance. They have intrinsic value as works of art, and are practically the only surviving examples of the famous lost paintings of classical antiquity. These works of art provide a vivid reflection of daily life in ancient times; through them we gain insight into the aesthetic experience of Rome and are able to see which themes were considered important in Roman society. Classical myths, elements from the theater, genre scenes, still lifes and sacred landscapes - all are depicted on the wall paintings. MOTIFS AND DESIGNS

MOTIFS AND DESIGNS THE TECHNIQUE OF ROMAN WALL PAINTING

THE TECHNIQUE OF ROMAN WALL PAINTING