|

…the only truth is an individual truth, which needs to be carefully preserved. (Jean Dubuffet,

Asphyxiating culture and other writings, (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1988), p.44)

By a strictly physical sense, a work is an entity consisting of material, time and space, the product of a process of physical creation. At this fundamental level, a work subsists within the same physical world within which all matter exists, and in so, abides by the same temporal rules. A work also acts as a mute witness to its past, unable to object to any alterations to its essence. The term ‘work’ used here is indicative of a physical presence of a being, though in an artwork are other, less concrete realms. These other states in an artwork are more abstract in nature, non-physical, illusional realms, seeming to transcend the temporal or material laws of the physical world. These other states represent something beyond the material surface, behaving similarly to a symbol. The subjective nature of these non-tangible states does not provide the same finite restrictions of materiality of the physical state in works. For this argument however, I will primarily focus on the physical being, from creation to death, in the material surface and material restrictions of an artwork.

|

Every work maintains a unique, original and non-repeatable place in space and time, abiding by the same laws of continual time, nature and decay as all other matter. Every work is essentially a product of a physical process, an assemblage of particular material, a point of time, and the space occupied by the material. Within these elements also subsist a work’s essence. After the point of creation the work exists as an entity that is independent of the mind. Existence is a continual process, and a continual perceptual experience. Works situated in museums have long held an illusion of timelessness, seeming to exist in a higher realm outside the mortal world (one could say within the walls of the ivory tower), and in this context do not appear to follow the rules of material temporality. In due time, all works must accept their own temporal state of material, and the ensuing total deterioration, or material death. Artworks communicate through the visual image, which, lacking word and language, signifies the relevance of the visual, material layer. The temporality of each work is due in part to nature and time’s effect and the physical determination of material of each work.

According to Martin Heidegger’s ‘The Origin of a Work of Art’, an authentic work exists within the parameters of a ‘virtuous circle’ (as summarized at http://www.panix.com/~squigle/vcs/heidegger-owasum.html, T R Quigley, 1996). Each work is an outcome of specific acts of consciousness, which results in the form of a physical product. The point of origin is the moment of creation, in the physical construction of material and the specific space occupied by the work, ‘from which and by which something is what it is and as it is’ (D Farrell Krell, Basic writings: Martin Heidegger, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 2002), p.143). After the point of creation, the authentic work is compelled to follow the circle, bound by its place in time, space and material. The boundaries of the circle physically constrain the work, sustaining the work’s true “thingness”. The completion of the circle is the material death of a work, unavoidable in spite of any illusion of permanence. The physical properties of every work precede the illusional, as any illusional properties are perceived through the material surface. Museum display and conservation work are usually more concerned with maintaining an illusion of a chosen immobile state rather than a work’s evolving material existence.

Although this standpoint denies a common idea of an artwork maintaining a higher status outside time and materiality, the physical boundaries of the work’s material limitations are realized simultaneously here with its aesthetic qualities, without any deception or alteration to the state of material and as such, the artwork is thus regarded as an object. Artworks in museums are rarely subjected to this kind of material treatment or regard, though these irreducible, fundamental elements of time, material and space are the very elements that lead to the completion of each work’s material destruction. The temporal limits of material can be realized, and in so, the limitations of being.

Truth and actuality exist within the work’s essence, in a work’s ‘thingness”. Restoration work tampers with the original essence, transforming the original qualities to create a new work. Alternative to restoration work is preventative conservation, which does not alter the work’s essence, but instead strives to balance environmental and structural problems of each work. At the minimal level of preventative conservation, works are stabilized against any possible decomposition or devaluing through the neutralization or elimination of harmful elements in the immediate environment and storage areas. Preventative methods can prolong the life of a work in a way that still retains authenticity.

Time and nature produce their own marks on the work in the course of the lifespan, also indicative of Heidegger’s “thingness” of a work. The “thingness” authenticates a work to its own existence, perhaps to remind the viewer and the work of its materiality and of its life. These marks are results of the experience and use of the work. A work’s “thingness” involves physical changes through experiences of time.

World-withdrawal and world-decay can never be undone. The works are no longer the works they were.

(D Farrell Krell (2002), op.cit., p.166)

The work retains its “thingness” by maintaining and preserving its specific place in time, space and material, whilst also displaying the consequences of time, activity and experience. In the course of a work’s circle, an indefinite number of authentic physical states occur over time, though the authentic work is one that bears its essence and all the physical changes. The continual changes in existence signify a static nature in viewing works over time as well.

Methods of display and art conservation have been likened to methods in science and medicine through the preservation of specimens. ‘The use of the vitrine in science and medicine is linked to the need to keep a specimen in a still viewable, arrested state of being’ (James Putnam, Art and artifact, (London: Thames and Hudson, 2001), p. 15). Hints of taxidermy processes can be found in the museum; works are suspended in time through methods of pickling, dehydration and neutralization in their respective sterilized environments. The arrested state of being, however, is another illusion, creating the appearance of a constant state and condition of being. Where museums have created illusions of timelessness and permanence, the actuality of life does not have definite in time, order or assurances of life or death, except for the assurance that time does not desist. Even within an arrested state, the constant experience of time will continue to create marks on a work.

The museum is an artificial environment, placing works under panes of glass and behind ropes, yet no amount of distance or illusion can deny the impermanent quality of all material. The museum withdraws the work from its world, attempting to displace or conceal a work from time and being. The viewer is often physically distanced from the work, by barriers such as pedestals, ropes or glass, attempting to avoid any contact to the physical realm of the work. In the voyeuristic distance between the work and the viewer, however, exists the truth or visual purity of the state of the material continually transmitted in the perception of the work. The concealment of display and assigned interpretations of works, in the feeling of completeness and totality, is often present in the chronologically and stylistically arranged layouts of museums. The unconcealment occurs in visual truth, life, and material condition of a work. The genuine experience of a work is in the work’s physicality, in the authentic condition of its material. The viewing event of a work takes place within the carefully placed stage set of the museum, often also provided with interpretation. Further, restorative methods create another undetectable layer of a visual lie, outside of a work’s original circle.

Ethical behavior

The museum’s role as guardian to works should also imply ethical behavior and the display of authentic, unaltered works. The expectations of the role and duties of the museum are difficult ones to prioritize, in that which functions provide the most relevance or applicability. Perhaps this role cannot be completely fulfilled in every aspect, though in the least, the museum has been socially expected to uphold certain ethical and moral obligations in its actions, as outlined in brief in many codes of ethics.

A work is a visual key for the viewer to the past, translated by contemporary interpretation and set in a particular context. A work is a piece of visual evidence, and if altered or falsified, will mislead as to its original essence. Works change in their significance and value through time, dependent on interpretations, context and society. The transformations of the natural, physical changes of a work, as well as the numerous interpretations, constantly renew works. Context and interpretation may change in different environments or time periods, as all truths of society, though the only verifiable truth of a work is the truth found in the authentic material and the state of visual honesty maintained by a work’s essence.

For a work to remain truthful to its own essence, certain moral and ethical principles, in addition to the physical ones previously mentioned, should be followed. The work that accurately presents its own current state of material, time and space discloses its true essence. The truth in, and of, being involves the ‘unconcealment’ (Krell, p. 176) of the authentic qualities of the work’s essence by maintaining the original essence. Processes of restoration work alter the original material, time and/or space of the work, signifying a transformation into a new, separate being. Science and technology have provided the illusion of exact chemical reproducibility, but have not yet admitted to the ethical implications of these alterations. The chemical make-up of paint or other material can be scientifically reproduced precisely at the basic chemical level, however the application of the reproduced material to the work is done within altered time and space. Likewise, science cannot reproduce aesthetic elements by any technical means, only the subjective hand or mind of the artist can complete this work.

Aesthetic qualities of artwork extend beyond the elemental configuration of material, entailing a complex set of human reactions to form, color, surface texture, etc. These cannot be analyzed or reproduced by scientific methods, for aesthetic values do not follow the logical laws of science. Attempts to recreate aesthetic values will never duplicate the original. At best, they offer a hint of the original work. An authentic work that sustains its lifespan, in its longevity, or brevity, is the most truthful to self, and to the viewer, in completion of its circle.

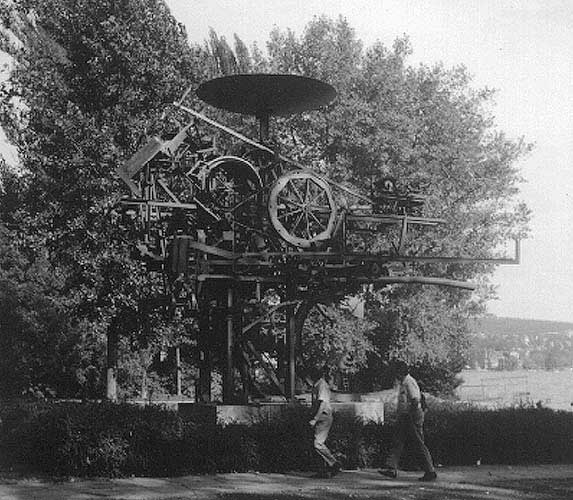

The activity and experience of a work, even within a displaced, listless state of a museum, have their effects; oil paints fade from their original color, metal corrodes, Jean Tinguely’s Homage to New York blows up. Time and the effects of time do not desist, regardless of any impression presented in many museums. A work is existent in our physical world, undergoing innumerable authentic physical states in the continual activity and experience of time. The condition of being transforms each work naturally, whilst still retaining its essence. Further, the physicality of the work is what affords the experience.

|

Conservation

Conservation work is carried out on a case-by-case basis, dependent on factors such as condition, value, time, money, staffing and urgency. Conservators first carry out condition reports on works, formulating long and short term plans for conservation work. A work is valued at this point not only in its physical condition, but also the social, historical and monetary significance. The application of science to artwork has its limitations in so far as sustaining material, time and space by technical means that still retain a work’s essence without adding superfluous elements or by alterations.

Ideally, each work has a running file of its condition, often updated at accession, before loaning or before display. At this point of interaction, a decision is then made regarding the worth of the conservation work in the relation to the work’s value weighing the time, efforts and monies required of the museum. After the state of condition is decided and a value assigned by conservators, an estimated life expectancy of a work can be predicted. In John Ashley Smith’s book, Assessing Risk Management, a break point in every work can be determined, where the minimum level of physical integrity is found. This is also about the same point defined by the Museums Association when the item can be deaccessioned or destroyed (Museum Association Code of Ethics Disposal, section 4A). A work that has fallen below its break point has lost its relevance and significance. Conservators have defined the level of integrity of a work to decrease through time, in the deterioration of material, as well as the value and/or historical and cultural significance. This integrity should also further extend to the visual obligation of maintaining the authentic essence of a work. Implementing all known methods of restoration could extend the life of a work to some degree, though the rate of decay will never cease. The decay and change of the work is not damage, but instead the on-going realization of a work’s own essence.

Ashley-Smith also advocates an increased responsibility of conservation and compiles a checklist, broad enough to relate to the individual work. Variations in the results of conservation work occur on a regular basis, in the differences of operation, in the working guidelines of each museum, and in the individual tastes, preferences and education of each conservator. When working within the subjective realm of an artwork, personal taste and perception are relevant factors. Recent trends in certain conservation departments include increased documentation and the responsibility of ethical obligation in all workings of the museum.

Another interesting idea in Assessing Risk Management is the determination of a time length of use and display for each work. The first consideration in stabilizing the environment and in the use of a work is prior even to any attempt of restorative work. Further, all points of restoration are checked and re-checked by a number of individuals. The understanding is then made of individual accountability to work taken, and also of the ethical implications of conservation work to future generations, as in conservation departments such as the Victoria and Albert Museum (interestingly headed by John Ashley-Smith), the responsibility of each conservator.

As the museum and its workers exist within the changing social constructs of our particular culture and time, the methods and ethics of conservation are also modified through the years. Each institution in theory maintains and enforces its own working guidelines of conservation and ethics, though certain museums have referred primarily to the codes set by organizations such as International Council of Museums (ICOM), the Museums Association, E.C.C.O., etc. as general guides. The codes of ethics for museums and conservators used by museums at best scratch the surface of the major ethical dilemmas resulting from conservation work, particularly regarding the art of this last century. These codes are weakly defined outlines, and do not provide ample specifics to the extents of preventative or restorative conservation work, although the complexity of setting ethical guidelines to restoration work is important to note.

As conservation work is done on a case-by-case basis, any attempt at a formulaic equation or a set of universal guidelines is ineffectual. Attempts at universal laws result in the loss of the individual nature of each work by applying generalized codes. Individuality cannot be categorized by broad, over-riding rules. Each work must fulfill the individual truth of its essence. At this point, no restrictions preventing over-restoration, over-paintings, or reconstructions, for example, exist in any applicable universal form. Effective ethical guidelines serve the difficult task of defining ethical problems in larger statements, while concurrently providing ample specifics for enforcement and applicability, which are also reviewed and renewed periodically.

Obligation

One of the key arguments common to many of these codes is the obligation to future generations through the conservation of culturally deemed worthy works. The Museum Association’s Code of Ethics states the responsibility of the museum includes the prevention of loss, damage or physical deterioration of any works. Destruction and death can be postponed, though never fully avoided, as the inevitable consequence of time and aging. A balance between preventing any possible material loss and maintaining a work’s integrity is found in preventative conservation, inside a stabilized environment whilst retaining the work’s circle and maximizing the aesthetic experience of a work.

Inherent in life is death. Within the condition of being is dying. This denial of death by museums sustains certain notions of illusion. In the museum’s presentation of restored works that are no longer representative of their original essence, what truths are being given then? Restored works display an assumed complete state of a work, as an illusion of the former. If a restored work essentializes an illusion of what was, or what is perceived to have been, the work’s visual (material) authenticity is altered in restorative processes. Each act of restoration removes the work further and further from its origin, and in so, from its essence, truth, and authenticity. The work thus presented is a reproduction of its former essence, emitting a false impression of the original state. Each work belongs to one reality, one essence, and one evolving appearance. Restoration work depreciates the original work by presenting a reconstruction, or a simulation of the original work. Our obligation to future generations is therefore visual truth, be it in a noticeably decaying Michelangelo drawing, or an ever-changing Anselm Kiefer work. Maintaining a work’s visual purity through time is to display its material truth.

Prevention vs. Restoration

To differentiate preventative and restorative conservation is in the action taken directly on the material surface of a work. Conservation work is not always strictly preventative or restorative per se, for some processes entail both types of conservation. Preventative methods strive to create and maintain a stable, sterilized environment and to provide a durable physical structure for a work, whilst maximizing the work’s use and retaining the work’s integrity. The goal of preventative conservation is to inhibit further damage and deterioration without physical alteration or addition on the material surface. This prevention extends then to the storage, exhibition, use, handling and transport of the work. Environmental factors such as light, humidity, temperature, pests and atmospheric pollution are monitored in the near clinical environment of the museum.

Restorative methods, on the other hand, recreate damaged or missing elements by material evidence such as photographs, condition reports, purchase agreements and sales records. Restorative conservation as defined in the UKIC handbook attempts ‘to recreate, in whole or part, the missing elements… based on historical, literary, graphic, pictorial, oral, archaeological and scientific evidence’ (p. 55), to a specifically chosen earlier state of a work. Reconstructive work is essentially subjective, as no methods of in-depth research can reproduce essence or individuality. As a work is continually restored, layer upon layer of subjective visual illusion is built.

Even a painstaking transmission of works to posterity, all scientific effort to regain them,

no longer reach the work’s own being, but only a remembrance of it. (D Farrell Krell (2002), p.193.)

Restoration work is a depreciation of the original work from its essence, a loss of its authenticity and meaning.

A contemporary identification is made with a point in the past that has attempted to be re-established, accomplished by artificial means. A fantasy in the museum has been built to give the impression that the works are immortal, immovable, unaging, set in their timeless surroundings. In restoration work, the marks of time and history are attempted to be physically erased from the work. The illusion of authentic works is translated in the presentation of restored works. A common unwritten rule followed by many conservators is the ‘6 and 6 rule’. From six feet away, the object appears to be in the original state to the ordinary passing viewer, yet from six inches the restoration work should be perceptible to either a professional or an extremely observant visitor. (Also explained in Andrew Oddy, ed., The Art of the conservator, (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992) p.11) However, this rule attempts to hide the restoration work, creating a simulated look of an authentic work by the use of similar colors, materials or replicated textures. The perceived illusion of the state of the original is often disguised, by the six and six rule and other methods, to attempt to become an imperceptible element. A seemingly flawless layer is presented as the complete, original work. (Alternatives have been to clearly distinguish the restoration work from the original by using contrasting color or material.)

As material change is not damage, but part of existence, death and destruction are not negative occurrences, but merely natural processes. Loss, material change and chance are inherent characteristics in the unpredictable nature of life. By every work’s eventual destruction, ‘… is the possibility of being becomes actual, in it beings fulfill their “determination” with birth is inclusive of eventual death’ (Herbert Marcuse, Hegel’s Ontology and the theory of historicity, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), p. 59). The determination of each work is in its need to complete and fulfill its material intentions.

True obligation

The experience of an authentic work is a primary obligation not only to our own time, but also to future generations. The experience of visual truth of the authentic work outweighs issues of endurance and longevity through restoration. This experience is not a singular, defined event, but is renewed moment-to-moment, by time, context, environment, condition or interpretation.

To burn always with this hard gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy is success in life.

(Walter Pater, The Renaissance, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1899), p. 250)

The sensation in the experience of the real, in the authentic state, is the experience of the intense ‘thingness’ of a work.

Can these ethical and moral commitments be put into usable and enforceable guidelines for museums? To generalize ethical issues would entail ignoring the physical intentions of the individual work, making any such universal guidelines useless. As conservation work is completed on a case-by-case basis, any attempt at ethical guidelines should follow suit, such as Ashley-Smith’s checklists for each individual work.

Perhaps, more effective, and the most visually authentic, is the exclusive use of preventative methods in conservation, but ultimately allowing each work to bear the marks of its own existence. An authentic work is a work which has retained the outer layer to its circle, its essence. Preventative conservation does not impede on this layer, but maintains it. Restorative conservation alters the visual layers by its processes.

All work as essentially existential beings. A work is a creation that is both physical and natural, within the bounds of mortality that even art cannot transcend. The physical boundaries of a work are known in the material limits of each medium, and in retaining its place in time and space.

Only to be sure it is passion- that it does yield you this fruit of a quickened, multiplied consciousness of this wisdom, the poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for art’s sake, has most; for art comes to you professing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moment’s sake. (Walter Pater (1899), p.252)

And in that moment of an authentic work, the experience of a fullness of essence transpires.