ANISTORITON

Issue P032 of 7 June 2003

A Minoan Vase from Zakros, Crete

The Sanctuary Rhyton

by

Karla Huebner

Ph.D cand. (Hist. Art)

University of Pittsburgh

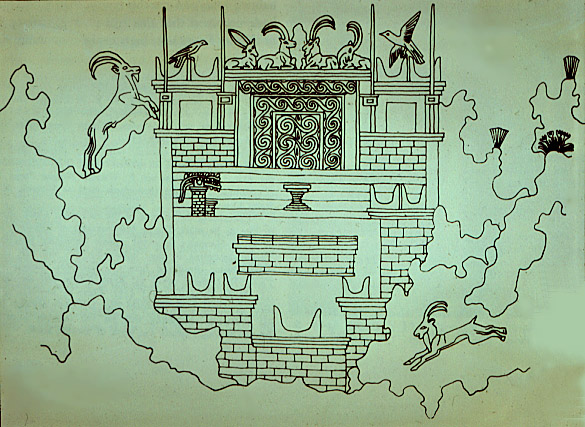

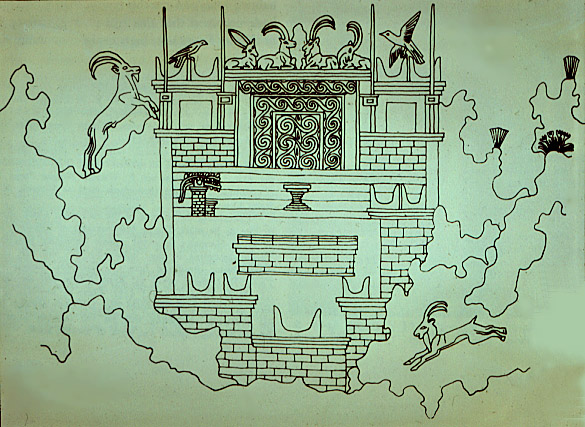

| The Sanctuary Rhyton, found in 1963 during the excavation of the palatial structure at Kato Zakros, exerts a fascination unique among Minoan artifacts. Less famous than the bull-leaping fresco at Knossos, less human than "La Parisienne" fresco, less baffling than the Phaistos disk, it nonetheless draws us into a mysterious and compelling world, a world in which an elaborate and commanding structure melds with a mountain landscape populated only by goats and birds.

|

| What is this structure, with its hieratic spirals, its crowning horns of consecration, its mazelike walls? What landscape is this, where birds and shy wild goats cavort and take possession of a manmade edifice? Whose place does this depict, and why? What, indeed, does this ritual vessel tell us of the Minoan world?

|

The Sanctuary Discovery at Zakros

The palace of Zakros, home to the Sanctuary Rhyton, lies in a green valley surrounded by violet mountains and leading toward a bay that is one of the safest of eastern Crete.[1] Not far from at least one peak sanctuary, it is one of the four canonical Minoan palaces, and is among the best preserved-especially in regard to its contents. Like the other palaces, it appears to have been destroyed at the end of the third phase of the Neo-palatial period by "a sudden catastrophe" followed by fire.[2]

The palace of Zakros, home to the Sanctuary Rhyton, lies in a green valley surrounded by violet mountains and leading toward a bay that is one of the safest of eastern Crete.[1] Not far from at least one peak sanctuary, it is one of the four canonical Minoan palaces, and is among the best preserved-especially in regard to its contents. Like the other palaces, it appears to have been destroyed at the end of the third phase of the Neo-palatial period by "a sudden catastrophe" followed by fire.[2]

Apart from some damage caused by farmers working the soil over the millenia, the palace at Zakros was undisturbed from its destruction to its excavation. There was little or no evidence of looting or reoccupation, and its excavator hypothesized that remaining inhabitants of the area had considered it an inviolable and sacred site.[3] This kind of taboo seems to have applied to several sites on Crete and in ancient Greece-the Mycenaean palace at Thebes was under sacred prohibition into the classical period,[4] and the much earlier House of Tiles at Lerna is probably a Early Helladic example. Such an attitude toward the ruins bolsters the view that these structures were above all religious in function, with their administrative and storage functions playing a supportive rather than a primary role. We are reminded of the monasteries and convents of the medieval period, where religious life was accompanied by gorgeous devotional items, the inhabitants were literate and included artists and craftspeople, and the organization exercised some control over the lives and crops of people living nearby. Among the areas excavated at Zakros were a small cult room, a lustral basin, some repositories, an archive, and a shrine treasury. Cult and household items were in their original positions in these rooms, and many of the items in the treasury, especially rhyta and chalices, were "admirably carved in a variety of choice stone."[5]

Yet the Sanctuary Rhyton was not found among the shrine treasures. Rather, it and a chlorite bull' s-head rhyton were found in pieces in a large nearby hall with lightwell and columns (the Hall of Ceremonies). Apparently the two rhyta had plunged from a similar hall on an upper floor, landing amidst "calcined debris fallen within the paved lightwell."6 Complicating matters, not all of the pieces of either rhyton were found in the lightwell, nor even in the Hall of Ceremonies. The lower part of the Sanctuary Rhyton was in the hall' s southwest corner; most of the collar was at the entrance of the north portico connecting the hall to the Central Court.7 Its gilded neck turned up amid the debris of a large semi-underground storeroom in the northwest wing, where the eleven or twelve pithoi and many mid-sized pots originally stored there had been pelted by hundreds of small pots, stone vases, and ritual paraphernalia falling from an upper floor.8 Supposedly the neck had been stored on this upper floor with the other ritual items (clay vessels and a bronze double axe) that cascaded into the storeroom when the building gave way.9 But although the northwestern storerooms and the rooms above them "were immediately connected" with the shrine area to the south, and these storerooms may have been used for shrine-related items 10 (perhaps less precious than those stored in the shrine treasury), this hardly explains why the gilded neck of the Sanctuary Rhyton ended up in a northwest-wing storeroom when the other pieces fell into the Hall of Ceremonies, just off the Central Court. Whether the rhyton was broken and the parts separated on the ground floor (and never fell from the upper storey at all), or it was broken and separated on the upper floor prior to falling, the scattering of its pieces makes us wonder exactly what happened.

Description

Let us now look more closely at the Sanctuary Rhyton itself. About a foot tall,11 graceful and well proportioned, it is a chlorite vessel created in three main pieces (body, neck, and collar). Holes for tenons indicate it also had a handle,12 perhaps of wood or even rope.13 The neck and rim retain traces of gilding, and very likely the entire vessel was gilded to give an impression of solid gold.14 It now exists, however, in contrasting sections of dark green and light brown, possibly the result of the broken pieces being burnt at different temperatures 15 or of chemical reactions to the combustion fumes of whatever was burning nearby. The rim has a pattern of curls or rosettes; the neck is smooth and concave; and the collar is ribbed. The body, of course, is what most catches our attention, with its all-over relief carving of a shrine, two birds, and six wild goats in what appears to be a rocky wilderness. It is unusual first in being a relief vessel at all (few survive, suggesting that relatively few were made), second in that nearly all of its pieces were found, and third in its subject.

Most surviving Aegean relief vessels were carved of black or green steatite or chlorite; some were gilded or employed polychrome materials.16 Both steatite and chlorite are soft stones abundant on Crete, although weathering has rendered present-day outcroppings too friable for sculpture.17 Only five Minoan and four Mycenaean sites have yielded stone relief vessels, whereas many offer plain; Knossos has the most examples, which leads to the as-yet unproven hypothesis that they were produced there. Many but not all of the vessels were found in LM1B destruction deposits. None were found in a treasury or tomb.18

These stone relief vessels depict combat, bull leaping, marine life, agriculture, scenes of uncertain meaning, and peak sanctuaries or activity at peak sanctuaries. No women are shown on the extant vessels. This may mean that they were used in specifically male ritual contexts,19 or it may merely reflect on the small number of remaining relief vessels. They are almost universally broken, and usually only fragments remain of any particular vessel. The Sanctuary Rhyton and the Harvester Vase are two of the most complete (though the latter lacks its lower half) and are certainly two of the most beautifully designed and skillfully executed.

While Minoan relief vessels are rare finds, skillfully carved stone vessels are not. The treasury of the shrine at Zakros, which is the only known example with in-situ contents (although its lack of objects made of precious metals has been blamed on priests or royalty carrying these away at the time of the destruction),20 was chock-full of splendid stone rhyta and chalices. Porphyry, veined marble, alabaster, basalt, and rock crystal were carved into a stunning variety of shapes. Sixteen conical rhyta alone graced the shrine treasury, along with calyx-shaped, horn-shaped, and ovoid rhyta, all expertly designed to capitalize on the decorative qualities of their materials.21

Use

How, one cannot help wondering, were rhyta used? What possible purpose could be served by a vessel with a hole in the side or bottom? Koehl has classified many shapes and types of rhyta, and suggests that although their basic function must relate more to "channeling or conducting" a liquid than to containing it,22 not all rhyta need have been used in a ritual context. He proposes that narrow-necked rhyta could have been used domestically to transfer liquids from big containers by plunging the rhyton into the liquid, allowing the rhyton to fill through its bottom hole, and then plugging the top hole with one' s thumb while carrying.23 Little or no liquid would then drain from the bottom hole en route, although it would still drip down the outer sides unless wiped away. Clearly, then, this method would be more feasible for water, beer, or even wine than for oil, perfumes, or honey.

Whether or not any rhyta were used thus in a domestic context, the Sanctuary Rhyton is generally considered a ritual vessel. Platon stresses the "exclusively cultic purpose of many rhyta with religious representations,"24 and while in some cases there might be uncertainty as to whether a rhyton' s imagery was religious, only one scholar seems to have questioned the nature of the imagery on the Sanctuary Rhyton.25 Large repositories of rhyta are typical of LMI palaces and towns, and the Neo-Palatial period saw an increase in "cult vessels, especially rhyta," stored thus. Use of precious metals for such vessels was common,26 and the fact that the Sanctuary Rhyton was elaborately carved in stone and then at least partly gilded disposes of any notion that it was a kitchen utensil.

How might the rhyton have been used in ritual, then? Lacking the kind of documentary evidence common for Egyptian and Mesopotamian practices, we know little of Minoan ritual beyond what can be inferred from art and excavation. One scholar suggests that Zakros chalices and rhyta "may represent drinking or pouring vessels for a banquet or investiture ceremony of the type represented on the later Campstool Fresco from Knossos."27

This seems plausible but perhaps too narrow in view of the many representations of rhyta in what seem to be other kinds of ceremony. The larnax from Ayia Triadha, for example, shows rhyta at a scene of animal sacrifice that may have been part of a funerary rite. Unfortunately, the only thing that seems definite is that rhyta were used in ceremonies, not what their significance and purpose within the ceremonies might have been. Perhaps transit through a rhyton was believed to purify or even transform a liquid.

Ritual Destruction?

Why is the rhyton broken, and why were its pieces scattered? Platon, its excavator, assumed that the Sanctuary Rhyton, along with the chlorite bull' s-head rhyton found near it, was damaged during or just after actual ceremonial use to propitiate the gods, concurrent with the destruction of the palatial structure at Kato Zakros. He envisioned the two rhyta brought out of the treasury for ceremonial use on the day Thera erupted,28 then shattered and dispersed in the earthquakes and tidal wave thought to have devastated Crete in the wake of the eruption.29 Archaeological opinion has abandoned the idea of a Theran tidal wave decimating the Minoan palaces, however, and some other explanation must therefore be found.

Rehak puts forth excellent arguments for ritual rather than natural destruction of bull' s-head and relief rhyta in general.30 Pointing out that only one such item has survived in its "original" state and that none show signs of repair as do some of the plain stone vases,31 he emphasizes that on bull' s-head rhyta, "the upper half of the muzzle is always missing" as though a live animal were being stunned prior to having his throat cut.32 These precious and beautiful objects, along with the inscribed libation tables common in peak sanctuaries, may have been used only once before being ceremonially destroyed. "What," he asks, "can make a more powerful effect than the deliberate destruction of such [precious] objects?"33 While ritual destruction is a tempting explanation for the fragmentary state of this class of object, it is not necessarily correct, or may only be correct in some instances. The rarity of relief vessels (compared to bull' s-head rhyta, of which there are about 23 34 ) makes it difficult to assign any particular theory to their breakage. Rehak himself states that since bull' s-head rhyta have not generally been found with other ritual vessels or in clearly cultic contexts, their function may have been different or even not cultic.35 Thus, even if bull' s-head rhyta were indeed ceremonially or ostentatiously destroyed, we cannot extrapolate with certainty to relief vessels with scenes, such as the Harvester Vase, the Chieftain' s Cup, or the Sanctuary Rhyton. The scattering of the Sanctuary Rhyton pieces within the rooms of Kato Zakros seems to fit better with Platon' s original hypothesis of damage and dispersal by a capricious natural force.

Another possibility is that breakage of these elaborate ritual vessels may have been entirely intentional but completely unceremonious. There have been many examples of this in the past 2000 years-the Byzantine Iconoclasts, Savonarola and his followers, Cromwell' s soldiers, and Mao' s Cultural Revolutionaries come to mind. Perhaps a popular revolution or religious reformation toppled the palatial theocracy. Fairly rapid transmission of news and plans could have occurred by sea, allowing conspirators to wreak havoc on a chosen date. Lack of corpses in the palaces merely indicates that either no one was killed during the destructions or that (more likely) survivors were able to bury their dead. If revolutionaries or reformers, or even the oft-suggested Mycenaeans, were responsible for palatial destruction, certain classes of ritual object may have been targets. Ritual items of gold and silver could be melted down for reuse, but works in stone could only be shattered or abandoned. The disappearance of most of the gilding from the Sanctuary Rhyton may mean that it was scraped or even melted off by people who realized the vessel was too light to be solid gold. Of course, this theory still does not explain why the pieces of the rhyton ended up in so many locations.

Similarity to Existing Sites

Does the Sanctuary Rhyton give us an accurate picture of Minoan sacred architecture? While there has been debate over what constitutes a peak sanctuary, and whether "hilltop shrines" are the same as peak sanctuaries (Watrous suggests that hilltop shrines may belong to the nearby community while the more rural peak sanctuaries served the entire region 36 and Van Leuven defines peak sanctuaries as those elevated above the surrounding territory 37 ), most researchers assume that the rhyton does give a general idea of how some extra-urban sacred sites looked. Van Leuven sees a resemblance to the Juktas sanctuary as seen from the east 38 while Lembessi and Muhly and Preziosi and Hitchcock have seen a resemblance to the Kato Syme sanctuary.39 (Exact correspondence to any particular site has not been proposed.) Shaw, meanwhile, has created a very well received perspective drawing of the structure shown on the rhyton.40

Ritual Activity at Extra-urban Sites

Much work has been done on peak and hillside sites. Wright believes peak sanctuaries were originally local cult sites that were later coopted by the palaces.41 Van Leuven classifies sanctuaries into domestic shrine, separate temple, pillar crypt, lustral basin, sacred repository, tree enclosure, and cave/peak/spring sanctuaries, but warns against making "dangerous distinctions" between private and public, urban and rural.42 Peak sanctuaries generally have deposits of votive offerings, and evidence of sacrifice is often present.

Use of Space/Perspective

Use of Space/Perspective

Perspective and use of visual space on the Sanctuary Rhyton have occasioned much discussion, not least because of people' s desire to extrapolate floor plans and elevations for sacred architecture from it. It is generally recognized that while the Minoans did not use vanishing-point perspective in their art, they did employ their own system of spatial convention,43 which we need to understand in order to make sense of their art. This is important both in terms of understanding seemingly ordinary matters like distance and depth (which we tend to forget are comprehended culturally rather than biologically), and more obviously cultural concepts such as hierarchy and iconographical significance. Sourvinou-Inwood reminds us that we must avoid letting our perceptual preconceptions distort our analysis of ancient art;44 in a like vein, Chapin suggests that if we think of art as "a visual language composed not of words, but of units of visual information," we can interpret Aegean landscapes by identifying the patterns in which the artists arranged their pictorial elements.45

Chapin, who has devoted considerable attention to the Aegean visual language, distinguishes first between peopled or "inhabited" landscapes such as that shown in the Gypsades rhyton fragment (which shows a man at a shrine), and "floral/faunal" landscapes such as those on the Sanctuary Rhyton and the Akrotiri Spring Fresco. Floral/faunal "pure" landscapes were rare in Western art before the Renaissance and thus their frequency in Bronze Age Aegean art is intriguing.46

Chapin then posits that Aegean art emphasizes "frontal, profile, and overhead views" with "individual parts represented in either frontal or profile views, thus creating a conceptual rather than perceptual representation" of the figure. (The fact that streams are presented from overhead is also seen as conceptual rather than perceptual.)47 The goat shown turning its head toward the viewer on the Sanctuary Rhyton is sometimes described as an attempt at foreshortening,48 but could just as well be considered an example of combined frontal and profile views.

Atmospheric perspective does not appear in Aegean art, but distant objects are sometimes shown slightly smaller. This can be seen on the rear horns of consecration on the Sanctuary Rhyton.49 Overlapping and vertical perspective do occur in Aegean art, and in this context Chapin cites Betancourt' s definitions of "shallow stage" and "distant stage" as important constructs for understanding Aegean scenes. "Shallow stage" involves limited depth of field and little overlapping, and is especially common on seals. "Deep stage" involves panoramic or "far away" vistas and allows for much more spatial complexity. (The Sanctuary Rhyton, the Siege Rhyton, and the Flotilla fresco are cited as examples of deep stage.50 ) To Betancourt' s classification Chapin adds a "median" stage for works like the Katsamba pyxis, and suggests that while modern viewers can grasp Aegean conventions of vertical perspective and overlapping, the lack of linear perspective, aerial perspective, and (usually) diminution of size ultimately confuses the modern viewer and leads to "conflicting interpretations" of how space is represented in Aegean art.51

What, then, are we seeing when we gaze upon the Sanctuary Rhyton landscape? Leaving aside questions of iconography and religious meaning, what are the characteristics of this scene? How tall, how deep, and how flat are these spaces? How big does our structure end up being, where is it really located, and what do the goats and birds contribute to our spatial understanding of their home?

Lacking linear perspective to express distance, the artist uses overlapping and "tilted perspective" to convey the shrine receding from view. But if the ground is "tilted," then how, asks Chapin, do we know whether the shrine is built on level ground tilted to express distance, or on a genuine hill?52 Additional information is required. Stylized rocks indicate a rough terrain here, while overlapping of sections of ground give us irregular areas at varying distances. Chapin believes the fact that "one landmass is behind and above the one immediately in front of it" reveals that the terrain does represent the expected hill or mountainside. This interpretation is reinforced by the presence of mountain goats and sky.53

The width of the tripartite shrine is indicated by the fact that four goats sit along the center top; the center is thus a minimum of four goat-lengths wide, or in other words perhaps about sixteen feet. Shaw reconstructs the side sections of the shrine as being at about the same depth as the center and interprets it as fronted by six steps and a long temenos area with central altar and a righthand-front entrance.54 This seems eminently likely, although it is unclear from the smooth floor of the temenos whether the shrine and its front walls are on level ground jutting out from the hillside, or slope downward, perhaps in terraces, with the surrounding terrain.

The tripartite shrine, which we interpret as a distant object, is shown "prominently on the widest part of the rhyton' s pictorial field," dominating the composition while the foreground architecture and landscape occupy a less commanding position on the lower slope of the rhyton. Chapin notes that this "flip-flop of emphasis from ' foreground' to ' background' ... challenges contemporary assumptions about the primacy of the foreground" and indicates Aegean artists did not favor foreground over background.55 With this observation we move from Aegean conventions of simple distance and orientation toward their meanings when used to create iconographies of hierarchy and religious symbolism. It seems safe to say that the tripartite shrine is the main focal point of the Sanctuary Rhyton, for while it may be in the ' background,' even today we instinctively respond to its central placement, its complexity and ornamentation, and the fact that the animals, temenos walls, and the very shape of the rhyton lead the eye directly toward it. These are all perceptual cues we share with the Minoans.56

What else can we deduce? Sourvinou-Inwood has shown that if "the content of a picture is articulated hierarchically" in a Minoan work, central objects and figures, especially those portrayed higher up in the picture, are hierarchically superior (just as tends to be the case in more recent Western art).57 This makes the tripartite shrine the most significant part of the overall shrine structure, a finding supported by the fact that Minoan and Mycenaean depictions of shrines are generally limited to a tripartite or even smaller shrine, not to an entire structure of which a shrine is a part. Similarly, the four goats seated atop the shrine become hierarchically superior to the leaping goat and the galloping goat, and even perhaps to the birds of the shrine side sections. This presents us with some intriguing possibilities in the interpretation of the animals' purpose.

Animal Imagery

Animal Imagery

Altogether, six goats and two birds populate the landscape on the Sanctuary Rhyton. In general their presence has been regarded as part of the scenery: that in essence a peak sanctuary can be expected to attract wildlife between human visits and that goats and birds signify the remote nature of the locale. Similarly, they have been taken as a shorthand for the deity of the shrine: that as seals and other artifacts show a goddess figure accompanied by animals (particularly goats and birds), this so-called Mistress of the Animals is therefore implied by unpeopled scenes of goats and birds.58 This is certainly possible; later Greek divinities had their specific animals (Athena and her owl, Hera and her lion and peacock). One scholar has proposed a somewhat different scenario. Arguing that no architectural remains have been found at most peak sanctuaries and that those found have been (with one exception) "very simple," Bloedow doubts that the Sanctuary Rhyton depicts a peak sanctuary at all 59 and instead proposes that the rhyton shows captive goats living at Zakros.60 These captive goats would, he posits, have less fear of humans than do the skittish wild ones, and therefore would have no qualms about climbing and sitting on manmade structures. They might even have been kept for milk.61

While captive goats may well have been kept at Zakros, permitting artists ample opportunity to observe their play and poses, it seems a bit much to say that while the rhyton "was most likely used for cultic purposes, it does not follow that the decoration on it is also of cultic significance."62 Everything we know about the Minoan world indicates that its religion was deeply bound to the natural world and that the lives of the people-at least those living in the palatial structures-were thoroughly intertwined with religious awareness and practice. The notion of a ritual vessel decorated with scenes devoid of religious content seems highly improbable. As mentioned earlier, archaeologists have disagreed on whether the term "peak sanctuary" includes only shrines on mountain tops or whether it should also refer to those merely above human habitations,63 and perhaps it simply makes more sense to call the edifice shown on the Sanctuary Rhyton a hillside shrine than a peak sanctuary.

There is some evidence that peak sanctuaries were visited seasonally by individuals and that hillside shrines were more elaborate and the sites of actual ceremonies. But without letting ourselves be distracted by the varieties of religious experience available at different types of Minoan sacred spaces, it seems important to note that the landscape on the Sanctuary Rhyton is constructed in a suspiciously hierarchical manner and, despite its absence of humans, more closely resembles some of the cult scenes shown on seals than it does scenes of animal life such as the cat-and-bird fresco or vases decorated with octopi. While Bloedow' s points about the naturalness of the goats' poses are well taken, 64 in Minoan art naturalness of pose or expression is a weak argument against religious significance. Not only are four goats symmetrically if naturally and not quite heraldically posed atop the shrine, but they are flanked by birds, which echoes the common scheme of a Master/Mistress of Animals flanked by creatures of one sort or another. This arrangement in itself suggests hierarchical superiority.65

But what of the two goats on the ground? Why are they left out of the hierarchy? The goat to the viewer' s left appears ready to leap onto the shrine, while the galloping goat to the viewer' s right is placed near what Shaw believes to be the temenos entrance (Shaw even describes the goat as "heading for the entrance to the shrine").66 Sourvinou-Inwood stresses the symbolic difference between left and right in Minoan art, stating that a figure to the right of a hierarchically superior figure is favored over a figure to the left.67 The right in question being the superior figure' s right rather than the viewer' s right, this puts the climbing or leaping goat at an advantage over the galloping goat-as does, incidentally, the leaping goat' s higher position on the rhyton.

Why should the leaping goat be favored over the galloping goat? To answer this question requires a greater knowledge of Minoan symbolism and iconography than we currently possess. However, if the goats are considered to belong to the goddess, perhaps in this instance they represent her worshippers. We know little of the philosophy underlying Minoan religion, yet the highly sophisticated nature of Minoan society and its complex ritual paraphernalia tell us that we are not dealing with a primitive fertility cult-important though fertility probably was in Minoan religion. Stages in the evolution of religion have been posited as 1) individualistic, 2) shamanic, 3) communal, and 4) ecclesiastical;68 and Minoan religion appears to be strongly ecclesiastical. Whole libraries of papyrus, parchment, or vellum religious writings may have burned or decomposed; alternatively, the Minoans, like the Druids, may have preferred an oral tradition involving prodigious memorization of possibly hermetic texts. We know merely that their beliefs were sufficiently complex as to involve shrines, votive offerings, multiple ritual acts and objects, mythological beings, and symbolism that mostly defies modern interpretation.

If we take the bold and perhaps foolhardy step of equating goats with people (not altogether unheard of in religious parable), the leaping goat may represent ecstatic intuition and the galloping goat may represent enlightenment reached through more reliable steps (entering the temenos via the gate and passing the two smaller altars before reaching the tripartite shrine). Many religions and sects favor direct enlightenment over earnest study, though generally both routes are acceptable. If this interpretation is correct, the frontal face of the seated goat nearest the leaping goat now becomes significant, for frontal faces are not only uncommon in Minoan art, but signify death and liminal states 69 --perhaps including sacred ecstasy.

The baetyl thought to exist in the midst of the seated goats-assuming it is not a mere accident of the breakage and restoration-gives us another clue. If baetyls have been correctly interpreted as aniconic representations of deities,70 then the goddess is already in the picture, flanked by her goats. The birds can be interpreted as representing "divine epiphany"71 and thus are yet another indicator of the possible complex sacred significance of the rhyton scene.

Ultimately, the Sanctuary Rhyton presents us not only with a unique work of ancient Aegean art, but with an opportunity to ask a wide variety of questions about Minoan society, art, and religion.

NOTES

1 Platon, N., Zakros: The Discovery of a Lost Palace of Ancient Crete. Charles Scribner' s Sons, NY (1971), 37, 40.

2 Ibid., 60-61.

3 Ibid., 88.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., 64. P.Rehak ("The Use and Destruction of Minoan Bull's Head Rhyta," in R. Laffineur and W.-D Niemeier [eds.],

Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum 12, 441), points out that the treasury does not connect

directly to the shrine and that "their functional relationship needs to be reexamined."

6 Platon, Zakros, 64-66, 158.

7 Ibid., 161.

8 Ibid., 104-108.

9 Ibid., 108.

10 Ibid., 114.

11 J.W. Shaw, "Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," American Journal of Archaeology 82, 1978, 432.

12 Platon, Zakros, 163-4.

13 Shaw ("Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," 433) suggests the holes were for suspension knobs.

14 Platon, Zakros, 164.

15 Ibid., 163.

16 Rehak, P., "The Ritual Destruction of Minoan Art," Archaeological News 19 (1994), 1.

17 M.J. Becker, "Minoan Sources for Steatite and Other Stones Used for Vases and Artifacts: A Preliminary Report, 30A

(1975), 242-262.

18 Rehak, "The Ritual Destruction of Minoan Art," 1-2.

19 Ibid., 2.

20 Platon, Zakros, 133.

21 Ibid., 135.

22 R. Koehl, "The Functions of Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta," R. Hagg and N. Marinatos, (eds) Sanctuaries and Cults

in the Aegean Bronze Age. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen (1981), 179.

23 Ibid., 183.

24 Discussion following R. Koehl, "The Functions of Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta," 187.

25 E.F. Bloedow, "The ' Sanctuary Rhyton' from Zakros: What Do the Goats Mean?" Annales d' archeologie d' archeologie

egeenne de l' Universite de Liege [Aegaeum 6] Liege 1990, 72. 26 Koehl, "The Functions of Aegean Bronze Age

Rhyta," 184-5. 27 P. Rehak, "The Use and Destruction of Minoan Bull's Head Rhyta," 441.

28 Platon, Zakros, 160-161

29 Ibid., 290-294.

30 Rehak, "The Use and Destruction of Minoan Bull's Head Rhyta," 435-460.

31 Rehak, "The Ritual Destruction of Minoan Art," 2.

32 Rehak, "The Use and Destruction of Minoan Bull's Head Rhyta," 442, 451.

33 Rehak, "The Ritual Destruction of Minoan Art," 3.

34 Ibid., 2.

35 Rehak, "The Use and Destruction of Minoan Bull's Head Rhyta," 441.

36 L. V. Watrous, "Some Observations on Minoan Peak Sanctuaries," in R. Laffineur and W-D. Niemeier,

eds., Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age [Aegaeum 12] (1995) II, 394.

37 J.C. Van Leuven, "Problems and Methods of Prehellenic Naology," in Hagg, R., and N. Marinatos, eds., Sanctuaries and

Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age (Stockholm 1981), 13.

38 Discussion following A. Karetsou, "The Peak Sanctuary of Mt. Juktas, in Hagg, R., and N. Marinatos, eds.,

Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age (Stockholm 1981), 153.

39 A. Lembessi, and P. Muhly, "Aspects of Minoan Cult. Sacred Enclosures. The Evidence from the Syme Sanctuary (Crete),"

Archaeologischer Anzeiger 3 (1990), 329; D. Preziosi, and L. Hitchcock, Aegean Art and Architecture. Oxford

University Press. (forthcoming).

40 Shaw, "Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," 436.

41 J.C. Wright, "The Archaeological Correlates of Religion: Case Studies in the Aegean," in R. Laffineur and

W.-D. Niemeier (eds.), Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. [Aegaeum 12]. II (1995), 347.

42 Van Leuven, "Problems and Methods of Prehellenic Naology," 12.

43 Chapin, A.P., Landscape and Space in Aegean Bronze Age Art (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill 1995), 19.

44 C. Sourvinou-Inwood, C., "Space in Late Minoan Religious Scenes in Glyptic - Some Remarks," in W. Muller, ed.,

Fragen und Probleme der bronzezeitlichen agaischen Glyptik [CMS Beiheft 3] (Berlin 1989) 242.

45 Chapin, A.P., Landscape and Space in Aegean Bronze Age Art, 37.

46 Ibid., 40-42. Sp. Marinatos (Excavations at Thera IV [1970 Season] [Athens 1971], 50, 53) even felt that

similarities between the rendering of rocks on the Spring Fresco and rocks on the Sanctuary Rhyton might indicate`

that both works depicted Theran geology.

47 Chapin, A.P., Landscape and Space in Aegean Bronze Age Art, 46.

48 Shaw, "Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," 437.

49 Chapin, A.P., Landscape and Space in Aegean Bronze Age Art, 49.

50 Ibid., 49-50.

51 Ibid., 51.

52 Ibid., 53.

53 Ibid., 85-86.

54 Shaw, "Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," 435-7.

55 Chapin, A.P., Landscape and Space in Aegean Bronze Age Art, 87-88.

56 Sourvinou-Inwood, C., "Space in Late Minoan Religious Scenes in Glyptic - Some Remarks," 246.

57 Ibid., 246.

58 Platon, Zakros, 166. Platon even refers to her as "Goddess of Wild Goats."

59 Bloedow, "The ' Sanctuary Rhyton' from Zakros: What Do the Goats Mean?" 62-63.

60 Ibid., 68.

61 Ibid., 76.

62 Ibid., 77.

63 Rutkowski, B., "Minoan Sanctuaries: The Topography and Architecture," in R. Laffineur, ed., Annales d' archeologie

egeenne de l' Universite de Liege 2 [Aegaeum 2] Liege 1988), 72.

64 Bloedow, "The ' Sanctuary Rhyton' from Zakros: What Do the Goats Mean?" 68-71.

65 Sourvinou-Inwood, C., "Space in Late Minoan Religious Scenes in Glyptic - Some Remarks," 247.

66 Shaw, "Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," 433.

67 Sourvinou-Inwood, C., "Space in Late Minoan Religious Scenes in Glyptic - Some Remarks," 249.

68 A. Wallace, Religion, An Anthropological View (1966), 75, 86-88, quoted in J.C. Wright, "The Archaeological Correlates

of Religion: Case Studies in the Aegean," 343.

69 Morgan, L. "Frontal Face and the Symbolism of Death in Aegean Glyptic," in W. Muller, ed., Corpus der Minoischen und

Mykenischen Siegel [CMS Beiheft 5] (Berlin 1995), 135-149.

70 J.B. Rutter, "Lesson 15: Minoan Religion," The Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean, The Foundation of the

Hellenic World and Dartmouth College, http://devlab.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/lessons/15.html.

71 Ibid.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I would like to thank the following members of the Aegeanet Discussion List who kindly suggested sources for me to look into:

Anne Chapin, Louise Hitchcock, Jon van Leuven, Brian Madigan, Soledad Milan, Nancy E.W. Symeonoglou, and Anastasia

Tsaliki.

Becker, M.J. "Minoan Sources for Steatite and Other Stones Used for Vases and Artifacts: A

Preliminary Report," 30A (1975), 242-262.

Bloedow, E.F., "The ' Sanctuary Rhyton' from Zakros: What Do the Goats Mean?" Annales

d' archeologie d' archeologie egeenne de l' Universite de Liege [Aegaeum 6] Liege (1990), 59-78.

Chapin, A.P., Landscape and Space in Aegean Bronze Age Art (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 1995).

D'Agata, A.L. "Late Minoan Crete and Horns of Consecration: A Symbol in Action," Aegaeum 8(1992), 247-255.

Dietrich, B.C. "Minoan Religion in the Context of the Aegean," in O. Krzyszkowska and L. Nixon, eds., Minoan Society (Bristol 1983), 55-60.

Driessen, J.M., and J.A. MacGillivray. "The Neopalatial Period in East Crete," Aegaeum 3 (1988), 99-111.

Forsdyke, J., "The 'Harvester Vase' of Hagia Triada," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 17 (1954), 1-9.

Gesell, G.C. "The Place of the Goddess in Minoan Society," in O. Krzyszkowska and L. Nixon, eds., Minoan Society (Bristol 1983), 93-99.

Hagg, R., and N. Marinatos, eds., Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age (Stockholm 1981).

Hooker, J.T., "Minoan Religion in the Late Palace Period," in O. Krzyszkowska and L. Nixon, eds., Minoan Society (Bristol 1983), 137-142.

Karetsou, A. "The Peak Sanctuary of Mt. Juktas, in Hagg, R., and N. Marinatos, eds., Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age (Stockholm 1981), 137-153.

Koehl, R. "The Functions of Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta," in Hagg, R. and Marinatos, N. (eds) Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen (1981), 179-187.

Krattenmaker, K. "Architecture in Glyptic Cult Scenes: the Minoan Examples," in W. Muller, ed., Corpus der Minoischen und Mykenischen Siegel [CMS Beiheft 5] (Berlin 1995), 117-133.

Lembessi, A. and Muhly, P. "Aspects of Minoan Cult. Sacred Enclosures. The Evidence from the Syme Sanctuary (Crete)," Archaeologischer Anzeiger 3 (1990), 315-336.

Marinatos, Sp. Excavations at Thera IV (1970 Season) (Athens 1971).

Morgan, L. "Frontal Face and the Symbolism of Death in Aegean Glyptic," in W. Muller, ed., Corpus der Minoischen und Mykenischen Siegel [CMS Beiheft 5] (Berlin 1995), 135-149.

Platon, N., "The Minoan Palaces: Centres of Organization of a Theocratic Social and Political System," in O. Krzyszkowska and L. Nixon, eds., Minoan Society (Bristol 1983), 273-276.

Platon, N., Zakros: The Discovery of a Lost Palace of Ancient Crete. Charles Scribner' s Sons, NY (1971).

Preziosi, D., and L. Hitchcock, Aegean Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. (forthcoming)

Rehak, P. "The Use and Destruction of Minoan Bull's Head Rhyta," in R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier (eds.), Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum Annales d' archeologie egeenne de l'Universite de Liege et UT-PASP 12. (Universite de Liege and University of Texas at Austin, 1995), 435-460.

Rehak, P., "The Ritual Destruction of Minoan Art," Archaeological News 19 (1994), 1-6.

Rutkowski, B., "Minoan Sanctuaries: The Topography and Architecture," in R. Laffineur, ed., Annales d' archeologie egeenne de l' Universite de Liege 2 [Aegaeum 2] Liege 1988), 71-98.

Rutter, J.B. The Prehistoric Archaeology of the Aegean, The Foundation of the Hellenic World and Dartmouth College, http://devlab.dartmouth.edu/history/bronze_age/

Shaw, J.W., "Evidence for the Minoan Tripartite Shrine," American Journal of Archaeology 82 (1978), 429-448.

Sourvinou-Inwood, C., "Space in Late Minoan Religious Scenes in Glyptic - Some Remarks," in W. Muller, ed., Fragen und Probleme der bronzezeitlichen agaischen Glyptik [CMS Beiheft 3] (Berlin 1989), 241-257.

Strasser, T. (1997) "Horns of Consecration or Rooftop Granaries," Aegaeum 16 (1997), 201-207.

Van Leuven, J.C. "Problems and Methods of Prehellenic Naology," in R. Hagg and N. Marinatos, eds., Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age (Stockholm 1981), 11-25.

Warren, P. "Minoan Crete and Ecstatic Religion: Preliminary Observations on the 1979 Excavations at Knossos," in R. Hagg and N. Marinatos, eds., Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age (Stockholm 1981), 155-167.

Watrous, L.V. "The Cave Sanctuary of Zeus at Psychro: A Study of Extra-Urban Sanctuaries in Minoan and Early Iron Age Crete," Aegaeum 15 (1996).

Watrous, L.V. "Some Observations on Minoan Peak Sanctuaries," in R. Laffineur and W-D. Niemeier, eds., Politeia:

Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age [Aegaeum 12] (1995) II, 393-403.

Wright, J.C. "The Archaeological Correlates of Religion: Case Studies in the Aegean," in R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier (eds.), Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum Annales d' archeologie egeenne de l'Universite de Liege et UT-PASP 12. (Universite de Liege and University of Texas at Austin, 1995), 341-348.

Back to Cover

Back to Cover

The palace of Zakros, home to the Sanctuary Rhyton, lies in a green valley surrounded by violet mountains and leading toward a bay that is one of the safest of eastern Crete.[1] Not far from at least one peak sanctuary, it is one of the four canonical Minoan palaces, and is among the best preserved-especially in regard to its contents. Like the other palaces, it appears to have been destroyed at the end of the third phase of the Neo-palatial period by "a sudden catastrophe" followed by fire.[2]

The palace of Zakros, home to the Sanctuary Rhyton, lies in a green valley surrounded by violet mountains and leading toward a bay that is one of the safest of eastern Crete.[1] Not far from at least one peak sanctuary, it is one of the four canonical Minoan palaces, and is among the best preserved-especially in regard to its contents. Like the other palaces, it appears to have been destroyed at the end of the third phase of the Neo-palatial period by "a sudden catastrophe" followed by fire.[2]  Use of Space/Perspective

Use of Space/Perspective Animal Imagery

Animal Imagery