ANISTORITON

Issue H032 of 1 June 2003

The Samaritans from the Biblical Times to the 21st Century

Guardians of the Faith

By

Norman A. Rubin

Journalist, Indep. Scholar

Jerusalem, Israel

The Samaritan Creed

"The unity of God, with Moses as His Prophet; the holiness of the Sabbath and the set feasts; and the Sanctity of Mount Gerizim" |

Most people know little about today's Samaritans. Many believe that the name refers to an ancient Biblical race of which no vestige survives. They are often surprised to learn that the Samaritans, who accept only the Pentateuch as Holy Writ, are a vital, intelligent group with a rich history and a distinctive language and literature, practicing their own form of worship and following age-old traditions and customs.

They claim direct descent from Ephraim and Manasseh, sons of Joseph, who entered the Promised Land with Joshua and settled in the Samaria region; while their priests stem from the tribe of Levi. The Samaritans rather resent the name by which they are known; preferring to call themselves "Shamerim" --in Hebrew, guardians-- for they contend that they have guarded the original Law of Moses, keeping it pure and unadulterated down the centuries.

They claim direct descent from Ephraim and Manasseh, sons of Joseph, who entered the Promised Land with Joshua and settled in the Samaria region; while their priests stem from the tribe of Levi. The Samaritans rather resent the name by which they are known; preferring to call themselves "Shamerim" --in Hebrew, guardians-- for they contend that they have guarded the original Law of Moses, keeping it pure and unadulterated down the centuries.

Their numbers are not large, and today less than five hundred are left of a great nation that is said to have been counted in hundreds of thousands --there were estimated to be over three-quarters of a million in the early part of the Christian era. About half of the remnant live on their ancestral site, close to Mount Gerizim (1), and the other half in Holon, near Tel Aviv.

To this day, the Samaritans adhere strictly to their ancient traditions of their religion. Their yearly Passover ceremonial of the sacrifice of the Paschal lamb on Mount Gerizim is a colorful event reminiscent of old custom practice in Jerusalem. The Samaritan Bible is written in the old Hebrew script and differs slightly from the Jewish tradition. Like the Jews, the Samaritans recognize the 613 laws of the Five Books of Moses. They also accept the book of Joshua, but they reject the writings of the prophets and the oral law (Talmud). They have a belief in Resurrection and in the Day of Judgment; and believe in the coming of the Messiah that "will proclaim the glory of the 'Shamerim'".

Like the Jews, Samaritans celebrate three main pilgrim festivals; Passover, Pentecost and Tabernacles. The Passover rites are carried out precisely according to the instruction in Leviticus 23:5: "In the fourteenth day between dusk and dark is the Lord's Passover." and from Exodus 12:3-5, "let each man take a lamb or kid for his family." (2)

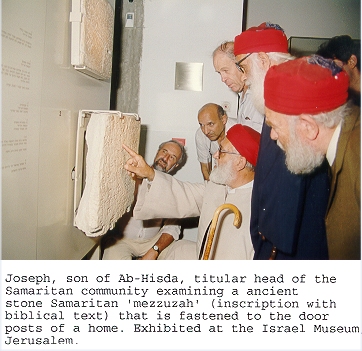

Samaritans celebrate the festival of Pentecost as the 'The time when the Israelites received the Law from Mt. Sinai', and in the celebration of the first fruits of tree and fields. On the Feast of Tabernacles, the traditional booth is put inside, as is the Jewish practice, for bitter experience across the ages has taught this vulnerable people the dangers of conspicuousness. (For the same reason, mezzusoth - metal or wooden cases enclosing small scrolls inscribed with two passages from Deutoronomy - are not fixed to door-jambs as in Jewish homes, but are hung inside.) Other holy days are the New Year (Rosh Hashanah), also considered Moses' birthday, which is celebrated for one day only, and The Fast of Atonement - when only infants below the age of one year are exempt from fasting.

The history of the Samaritans stems from Biblical narrative. General opinion amongst historians and Biblical scholars was that when the Northern Kingdom of Israel was conquered by Assyrians in 721 BC and its population carried off into exile, "the king of Assyria brought people from Babylon, Cuthah, Avva, Hamath, and Sepharvaim, and settled them in the cities of Samaria in place of the Israelites.." (2 Kings 17:24). These foreign elements who "paid homage to the Lord while at the same time they served their gods, according to the custom of their nations", are held to be the forefathers of the Samaritans.

Its motley collection of inhabitants became known as "Samaritans", which became a term of abuse, and expression of abhorrence. They were despised not only on religious grounds but also as individuals; "for the Jews have no dealing with Samaritans."(John 4:9). It was only when Jesus told the story of the Good Samaritan. He turned this term of abuse into a byword of Christian charity.

Friction quickly developed between the Samaritans and the Jewish exiles returning from Babylon in the fifth century B.C. The homecoming exiles, led by Ezra and Nehemiah, began to rebuild Jerusalem and the Temple, arousing the wrath of Sanballat, governor of Samaria, who "jeered at the Jews front of his companions and garrison in Samaria." - Ezra 4. For the Samaritans, allied with neighboring tribes, wanted to stop the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem by every means in their power (3). But, failing in their plans to harm the Jews, the Samaritans chose Mount Gerizim as their holy place, and later established their temple there. For the Samaritans the Biblical injunction in Deuteronomy is incontestable, "When the Lord your God brings you in the land....there on Mount Gerizim you shall pronounce the blessing." (11:29)

Feelings were further embittered by the unproven Samaritan claim that Ezra the Scribe had altered the script and the text of the Pentateuch. According to the Samaritans, their version is the original one, although basically it is the same as the Pentateuch of the Old Testament. The principal divergence is the telescoping of the first two Commandments, and the replacement of the tenth by one stressing the sanctity of Mount Gerizim as the site of House of God, the place of creation of Adam and Eve, and of the readying of Isaac for sacrifice.

Samaritan-Jewish enmity was heightened throughout the third century B.C., and flared into open conflict under the Maccabees. The climax came at the end of the second century B.C., when the Hasmoneon king, John Hyrcaneus, captured Samaria and destroyed its temple on Mount Gerizim. It was rebuilt in 56 BC by Gabinus, governor of Syria.

The Samaritans shared the bitter lot of the Jews under the rule of the Roman emperors Vespasian (AD 79-81) and Hadrian (AD 117-138). Under the rule of Emperor Hadrian there began a systematic destruction of Samaritan manuscripts --and erosion which continued for centuries, and it was he who built the temple to Zeus on the ruins of the Samaritan sanctuary on Mount Gerizim.

The Samaritans shared the bitter lot of the Jews under the rule of the Roman emperors Vespasian (AD 79-81) and Hadrian (AD 117-138). Under the rule of Emperor Hadrian there began a systematic destruction of Samaritan manuscripts --and erosion which continued for centuries, and it was he who built the temple to Zeus on the ruins of the Samaritan sanctuary on Mount Gerizim.

When the land came under the rule Byzantine kings, the persecutions continued; the rebuilt Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim was again destroyed. Twenty thousand Samaritans perished in the revolt against the Byzantine ruler Justinian I in 572. His successor deprived them of all rights and forced many to embrace Christianity.

The Arab conquest of Palestine in the seventh century and the short reign of the Crusaders in the eleventh and twelfth centuries saw the further dwindling of their numbers. During Crusader times, the population dropped to fifty thousand. After four hundred years of Ottoman rule (1516-1917), the sect had disappeared almost completely. By the end of World War I, only 160 remain, men still outnumbering women by nearly two to one - often the sign of a vanishing society.

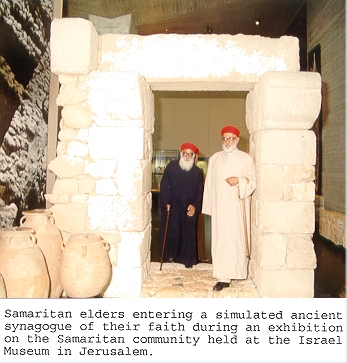

The turning point of Samaritan community came after the Israeli War of Independence: In 1949, due to efforts of Israel president Yitzhak Ben Zvi, they were recognized as citizens of Israel under the Law of Return. His encouragement prompted some of the Samaritan brethren from Nablus to join families in Jaffa and then move to Holon, where a housing project was set up and a synagogue consecrated.

The Samaritans, these Guardians of the Faith (4), have clung steadfastly to their belief in God, their hallowed Mount Gerizim, and in the punctilious fulfillment of all precepts of the Five Books of Moses. Having proved themselves wise, industrious and adaptable, the Samaritans confront a range of positive challenges altogether without precedent in their almost three millennia of history.

NOTES

(1) It is from Josephus, the Roman-Jewish historian that we learn that the Samaritans offered their help to Alexander the Great, and received in return permission to build a temple of their own on Mt. Gerizim.

(2) Ten days before the Passover festival, each family gathers in its own stone croft at the foot of the Mount Gerizim, bringing with a sacrificial lamb. On the appointed evening, the men dress in white robes and enact the biddings of Exodus 12:11, that "This is the way in which you must eat; you shall have your belt fastened, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand.", in remembrance of the hurried exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. While prayers are chanted, the paschal lambs are ritually slaughtered on the hillside and 'roasted with fire'.

(3) Sanballat's opposition was purely political. Although he had a Babylonian name, his sons, whom it is known from Elephantine Papyri, had Jewish names showing them to be worshippers of Yaweh.

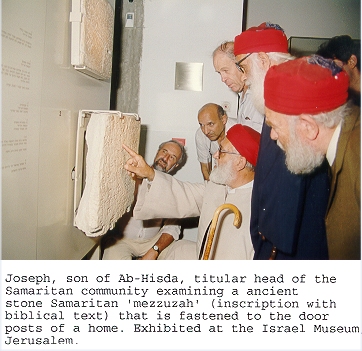

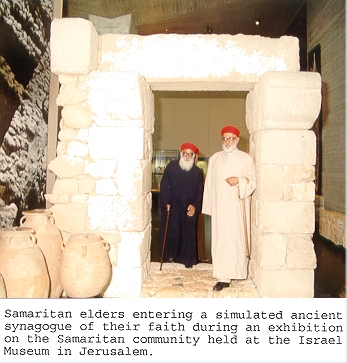

(4) Samaritan priests have a special place in the community. Originally descendants of Aaron, today they are of the Levite lineage of the sons of Uzziel ben Kohath ben Levi, for in 1624 the last high priest of the line of Aaron, Shalmah be Phineas, died without male issue. They cut neither their hair nor their beards, wear voluminous cloaks and red turbans, and apply themselves to religious affairs, subsisting on the tithe given them by the community.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Samaritans. Guardians of the Faith by Sylvia Mann.

"The Archaeology of Palestine. The Biblical Period" in J. Gray Peake's Commentary of the Bible.

The New English Bible from Oxford University Press.

Jewish Encyclopedia edited by Naomi Ben-Asher and Hayim Leaf, Shengold Publishers, New York.

Back to Cover

Back to Cover

They claim direct descent from Ephraim and Manasseh, sons of Joseph, who entered the Promised Land with Joshua and settled in the Samaria region; while their priests stem from the tribe of Levi. The Samaritans rather resent the name by which they are known; preferring to call themselves "Shamerim" --in Hebrew, guardians-- for they contend that they have guarded the original Law of Moses, keeping it pure and unadulterated down the centuries.

They claim direct descent from Ephraim and Manasseh, sons of Joseph, who entered the Promised Land with Joshua and settled in the Samaria region; while their priests stem from the tribe of Levi. The Samaritans rather resent the name by which they are known; preferring to call themselves "Shamerim" --in Hebrew, guardians-- for they contend that they have guarded the original Law of Moses, keeping it pure and unadulterated down the centuries. The Samaritans shared the bitter lot of the Jews under the rule of the Roman emperors Vespasian (AD 79-81) and Hadrian (AD 117-138). Under the rule of Emperor Hadrian there began a systematic destruction of Samaritan manuscripts --and erosion which continued for centuries, and it was he who built the temple to Zeus on the ruins of the Samaritan sanctuary on Mount Gerizim.

The Samaritans shared the bitter lot of the Jews under the rule of the Roman emperors Vespasian (AD 79-81) and Hadrian (AD 117-138). Under the rule of Emperor Hadrian there began a systematic destruction of Samaritan manuscripts --and erosion which continued for centuries, and it was he who built the temple to Zeus on the ruins of the Samaritan sanctuary on Mount Gerizim.