|

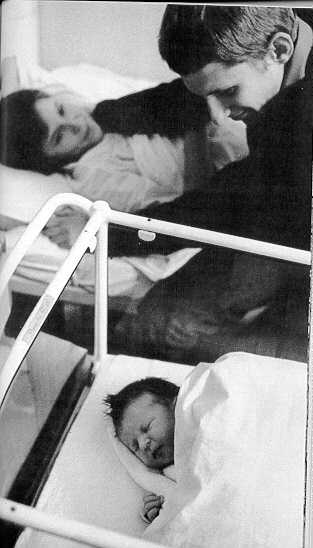

Note: Pictures have been taken from an official 1970s publication of GDR (East Germany)

The history of East Germany, the communist part of divided Germany, is nowadays explored more thoroughly especially after East German Archives were made available to researchers. In the February 1997 issue of The American Historical Review, assistant professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University, Donna Harsch, explores "Society, the State, and Abortion in East Germany 1950-1972".

Prof. Harsch begins her article by writing that on March 9,1972, the legislature of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) legalized abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. Other East Block countries had liberalized abortion laws in the late 1950s. The GDR, however, introduced liberalization in the midst of the wave of abortion reform that swept over the democratic, capitalist West from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. Despite its timing, the East German case was interpreted as a Communist reform and examined, when at all, with the methods peculiar to the analysis of socialist regimes. One can understand why. The vote in the People's Chamber was prompted not by public discussion, much less a popular movement, but by decision of the Politburo, ruling body of the Socialist Unity Party (SED). Thus scholars considered abortion reform almost exclusively from the perspective of Erich Honecker, recently ensconced as First Secretary of the Politburo, and treated it as one piece of the social policies (such as benefits for working mothers) he introduced. His "New Course" was intended, they explained, to bring the GDR into closer alignment with the Socialist Block, to demonstrate the GDR's ideological commitment to women's equality, and to institute social policies that met more of the real needs of East Germans. Whichever motive they underscored, commentators paid scant attention to the domestic context of legalization and, in particular, to the social repercussions of the restrictive abortion policy that preceded it, if only because few data were available to them.

|

In the conclusion she claims that the German communists created a one-party state that managed all aspects of public life and repressed individual freedom. They did so with the intent of transforming the society over which they ruled and forging a "New Socialist Man." The history of the failure, reform, and repeal of Article 11 proves, however, that there were always limits to the state's ability to control private behavior and to its desire to suppress the sovereignty of medical experts. Moreover, political goals, economic exigencies, social claims, and individual desires interacted in ways that increased the limits on the state's power to implement its original agenda. Gradually, a new pragmatism and belief in reform displaced the primacy of ideology, hectic economic and social transformations, and the pressure on workers to produce that had provoked the workers' uprising of 1953 and the massive emigration of professionals throughout the decade.

|

Especially after the party elite had isolated East Germans behind the Berlin Wall, the SED came to take significantly greater account of the nonpolitical aspirations of the people and to reward occupational achievements without requiring evidence of correct political consciousness. Most citizens resigned themselves to Communist rule and many worked actively to integrate themselves into an apparently permanent state of affairs. The state pulled back from its unsuccessful attempt to control even aspect of their lives; the "niche society" for which the GDR became renowned in the 1970s began to thrive. Certainly, the SED elite controlled the framework within which accommodation occurred. The abandonment of abortion reform in favor of the repeal of Article 11 demonstrates, however, that intentional pressures from below and outside the ruling circle could influence the kind of accommodation it had to make. The above points make clear that historians have to place the legalization of abortion in the GDR in its Communist context. This perspective, however, does not explain why the German Communist reform coincided with the wave of liberalization that swept the Western industrialized world and why it shared important features of the content and process in the West. Rather than look at political structure, property relations, or national culture, we need to focus on a variable that is key to the experience of women and that changed in the period under consideration-that is, the nature, degree, and social meaning of women's waged work. By 1970, East German women had attained the world's highest percentage of female participation in an industrial work force. An extremely high ratio of mothers with young children worked outside the home. Women were moving into more skilled jobs at a rapid rate. The demographic effects of German history, on the one hand, and the peculiar problems of socialized production, on the other, were largely responsible for these trends. East Germans shared the honors, however, with women in fast-changing market economies. Their employment's rapid pace of growth, its type and quality, and, above all, its extension across their entire adult lives evolved in tandem with the course of women's work in, especially, the United States and France in the 1960s. The analogous social experiences of the new breed of worker-mothers surely helps explain why the language of, first, public hygiene and, then, reproductive rights emerged at the same time in East and West. [...]

In No 2 of the German History 1997 Journal, Raymond Stokes of the University of Glasgow published an article on the combination of technology and ideology in East Germany. In the introductory part of his paper Stokes writes that Because of war time destruction, post-war disruption, Soviet dismantling, growing Cold War tensions, German division, and the need to establish institutions and procedures through which to govern the newly created GDR, few gave much systematic thought to the idea of establishing socialist technology until the early 1950s. As they began serious deliberations, party officials soon encountered two sets of perplexing issues. In order to accomplish their primary task-i.e. to define the difference (and superiority) of socialist technology in comparison to its capitalist counterpart-they needed, first, to adapt historical precedents to the situation of the GDR and, second, to address a range of thorny ideological and practical issues.

Nothing should have been easier than finding and adapting historical precedents for socialist technology, since in the early 1950s only one state, the USSR, had any long-term experience with this and since Soviet influence on the GDR was both direct and profound. Unfortunately for GDR planners, and despite considerable effort expended in this cause, they found little to help them in Soviet history. Part of the problem was that Soviet attempts to define socialist technology were at best ambivalent, if not downright contradictory. Throughout Soviet history, prevailing practice vacillated, often wildly, between a traditionalist wing (which stressed danger from the West, militarily as well as technologically; claimed high Soviet technological capability; emphasized military technology; and was largely autarkic) and a non-traditionalist faction, diametrically opposed to the traditionalist group. The non-traditionalists minimized danger from the West, accepted Soviet technological limitations, stressed civilian technology, and were open to outside influences. It was unclear which faction might hold the key to development of a specifically `socialist technology'.

|

He concludes his article by claiming that what becomes particularly clear through this story is that, although the idea of á `socialist artefact' never really bore fruit, a recognizably `eastern bloc technological style' for artefacts produced under the real existing socialist system did emerge, something well presented in a recent book on SED-Schones Einheits Design. Influenced primarily by centralized planning and its consequences, the GDR and other eastern-bloc countries produced both consumer and producer goods which were frequently disappointing in design and/or quality. These artefacts in turn influenced politics in the eastern bloc: inferior consumer goods made it difficult to motivate managers or workers through material enticements, while inferior producer goods ensured the production of more of the same.

Despite the fact that GDR planners appear to have searched in vain for the socialist artefact, it appears from this case study that both versions of Langdon Winner's question have to be answered in the affirmative. Politics (although perhaps not ideologies) do have artefacts. And artefacts certainly do have politics.