ANISTORITON

History, Archaeology, ArtHistory

V981 3 January 1998

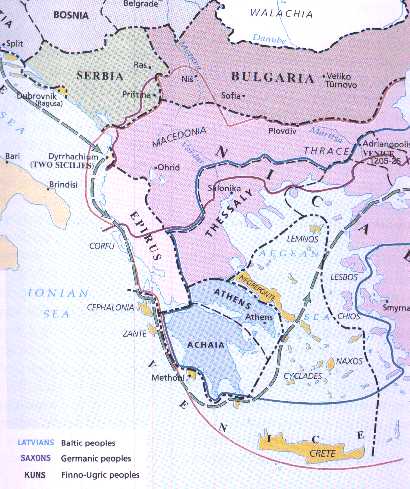

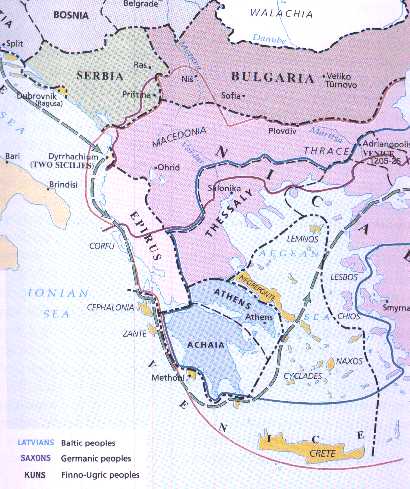

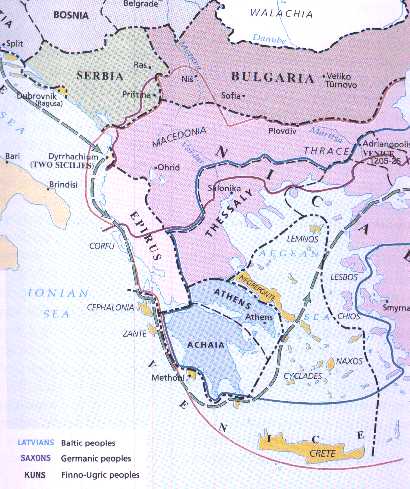

The Despotate of Epirus under Michael I (13th c.)

The Despotate of Epirus c. 1250 |

by

Katerina Kotsidimou

The Despotate of Epiros or Epirus was one of the many by-products of the Fourth Crusade and the capture of Constantinople by the Latins in 1204. The dismemberment of the Byzantine Empire by the Crusaders and the collapse of its capital led to a state of confusion and anarchy in the provinces. Refugees from the capital, provincial governors, and mere adventurers were able, with varying success, to profit from the situation and glorify their opportunism with an aura of patriotic fervour by establishing a number of succession states. Witnin this context, in Asia Minor a relative of the last reigning dynasty in Constantinople, the Komneni, set himself up as "Emperor in exile" at Nicaea and claimed rights as lawful heir to the throne of Byzantium. In mainland Greece another mamber of the same family succeeded in saving a corner of his country from the invaders and organized an independent state in Epiros, behind the secure barrier of the Pindos mountains. Eventually, the Despotate of Epiros was transformed from a mere resistance movement into a kingdom, whose ruler proudly adopted the title of Emperor of the Romans in defiance of the self-appointed Emperor at Nicaea; and the overthrow of the Latin Empire and the recovery of Constantinople became its aim.

The Despotate of Epiros was strengthened and gained in prestige during the reign of the dynasty of Angeli-Komneni. Especially under Michael I, the founder of the Despotate, Epiros was glorified. His conquests paved the way for the victorious campaigns of his successors which developed in existence of the Latin Empire.

Michael Angelos Komnenos Doukas was an illegitimate son of john Angelos Komnenos, the Sebastokrator, and first cousin of the Emperors Isaac II and Alexios III. His father hed received the title of Sebastokrator from Isaac II. In the course of his career he had held office under the Empire as governor of the districts of Epiros and Thessaly with the title of Dux.

Michael's claim to relationship with the imperial families of Byzantium may be thought questionable since he was an illegitimate child. But he did not hesitate to adopt the high-sounding title of Angelos Komnenos Doukas which he considered to be his inheritance from his father and from his brothers' mother, Zoe Doukaina. Nonetheless, his connections with Epiros were better substantiated. Michael was brought into contact with the district over which he was to rule through his father's career as governor of Epiros and Thessaly. Before the Latin conquest he had strengthened his hereditary interest there by marrying a relative of the governor of the Theme of Nikopolis.

Before 1204 Michael's career is barely known. However, there is certain evidence that he was acting as governor of the Theme of Peloponnese. In this capacity he worked for the furtherance of his own interests. He took part in several expeditions against the Latins. Eventually, he succeeded in asserting his authority as self-appointed governor in Epiros.

In the spring of 1205 Michael raised an army to fight the Crusaders in Peloponnese where they had met little resistance. The towns of the Morea had quickly collapsed before the combined armies of Boniface and Geoffrey of Villehardouin, two Frankish knights. The whole of the western coast-line was paying homage to the Franks. Michael Angelos was called to defendhis rights as governor of the Theme of Peloponnese. He fought the battle of Koundoura, but his army was beaten back by the knights and took to flight. Deprived of his authority over the Morea, Michael returned to Epiros to defend the north-west of Greece against the invaders and lay the foundations of the Despotate of Epiros.

Michael I set himself up as an autonomous ruler. His status was raised from that of the mere adventurer to the one of the last remaining champion of Hellenism on Greek soil, due to the fact that the Crusaders were victorious throughout the rest of Greece. He came to be seen as the protector of the traditions and defender of the faith of Byzantium. Actually, in order to emphasize his new dignity, Michael adopted the title of Despot which ranked next to that of the Emperor himself. As the first cousin of two Emperors, he could lay some claim to the imperial rank.

It appears that Michael had established his supremacy in Epiros without opposition and was now eager to save his territory from the Latins. In this effort he easily found soldiers within the Epirote, as well as the refugee population that had fled to Epiros after the invasion of the Latins into their areas.

At this point it is important to see over what part of Greece Michael's authority laid. By 1205 he was acknowledged over north-western Epiros, from Arta and the Ambracian Gulf to the Akrokeraunian promontory, and from Vonitsa through Akarnania and Aitolia as far south as Naupaktos. The geographical nature of Epiros makes it a district particularly suitable for the maintenance of an independent state. As the scholar Gregoras observes, Michael was far removed from the centre of affairs and confident in the natural strength of his own country (qtd. in Nicol, 1957, 16).

In th eearly years of its history the Despotate was little troubled with the Crusaders. The Lombards of the Kingdom of Thessalonike and Thessaly and the Franks of Athens and Peloponnese were too busy consolidating their own conquests. Additionally, the Pindos mountains effectively separated them from the Despotate. Actually, they did not have any real claim over Epiros and Albania due to the Partition Treaty of 1204 which granted to Venice many Epirote and Albanian territories. Hence, it was the Venetians rather than the Crusaders who were Michael's most dangerous enemies.

As a general rule it was against the policy of the Venetians to go to the trouble and expence of conquest and occupationin foreign countries. With Michael Angelos established as the Despot of Epiros, an arrangement could be made whereby he would govern his country in the name and the interests of Venice. From Michael's point of view such an arrangement had much to commend it. The Venetian merchants were long acquainted with Epiros and were not, therefore, regarded with the same hostilityas the intruding Franks. To make the pretence of holding his territory as a fief from Venice would prevent the Despotate from becoming a battle-ground, and compromise the claims of the Latin Emperor. Moreover, to allow the Venetians freedom of access to the markets of the Despotate would help its prosperity. Subsequently, an agreement was drawn between "Michael Comnanus Dux" and the Doge Pietro Ziani in June 1210 to the satisfaction and benefit of both. In that year, due to the skillful handlings of Michael, the Despotate became the base for an offensive campaign against the enemies of the Greeks, an independent state whose boundaries were steadily extended at the expense of Franks, Lombards, and Venetians. The agreement with the Doge was soon revealed as nothing more than the diplomatic preliminary to a declaration of war.

Only three years later that agreement became a dead letter. Durazzo was brought again under a Greek governor and Corfu was added to the Despotate of Epiros. In 1213 Michael launched his attack on Durazzo and the Venetian garrison was forced to withdraw. This was especially important because this way the overland route from the Adriatic to Thessalonike closed and the Latins there were deprived of reinforcements. After having taken possession of Venice's most valuable territory in mainland Epiros, Michael turned to the conquest of Corfu. He encouraged the Corfiotes to be loyal to the Despotate by renewing certain privileges granted to them by the Emperor Isaac II. The inclusion of the island in the Despotate may most probably be dated to 1214.

Nevertheless, Michael Angelos had to face also the largest Frankish army yet seen in Greece. In the summer of 1209 an immediate danger came to the Despotate from the Kingdom of Thessalonike whose barons had already claimed the right to exercise authority over Epiros. Michael managed diplomatically to avert the threat by concluding a treaty with Emperor Henry, which however was soon broken. In the summer of 1210 the Despot opened his first offensive in the region of Thessalonike. In this campaign he was soon joined by a Bulgarian adventurer called Dobromir Strez. Their joined forces and combined attacks on Thessalonike proved so effective that Henry had to struggle hard to defend his Kingdom. Eventually, after several months, Michael and Strez were forced to retire with heavy losses.

Michael Angelos proceeded with the further establishment of his rule over territories in northern Sterea and Thessaly. He faced the French baron of Salona successfully and added Salona to his territory. This secured his hold of Naupaktos, while it convinced the neighbouring Frankish knights of the strength of the Epirote armies. Michael then prepared for an attack on the less ably defended Italian fortresses in Thessaly. The principal strongholds of the Latins in this area appear to have been Larisa, Halmyros, and Velestino. At the time of Michael's invasion in Thessaly the defense of these fortresses was far from secure.

In the spring of 1212 Michael led his attack into the Thessalian plain. The Lombard knights seem to have offered little resistance and within a year the Epirote army had reached as far as the Gulf of Volos. By June 1212 the town of Larisa was again under Greek authority. The capture of Larisa seriously hindered communications by land between Thessalonike and the Latin states in the south. The Despotate now extended from the Ionian to the Aegean Sea.

Michael I did not live to pursue his conquests further. At the climax of his career he was murdered in his sleep by one of his servants. The date was most probably towards the end of 1215. When he died the Despotate included the whole of the Epirote and Akarnanian coast from Durazzo to Naupaktos, the islands of Corfu and Leukas, and on the east Larisa, Salona, and some parts of central Thessaly. On the north its Boundaries with the Bulgarian Empire were still hardly defined, But Michael had established friendly relationships with the chieftains of Albania. Venice had been deprived of Corfu and Durazzo. The threat of invasion by the Lombards of Thessalonike had been removed. The Duchy of Athens and Thebes had been virtually isolated from Thessalonike by the capture of Larisa and the extension of the Frankish power towards Naupaktos had been forestalled by the victory of Salona.

The Despotate of Epiros proved to be a threat to Thessalonike rather than to the heart of the Latin Empire and its ruler's attentions were divided between east and west. The armies of the Despotate had succeeded in gaining a prestige for Epiros which was to excite the envy of Nicaea. Michael's conquests helped in maintaining the Greek populations of the western areas of Greece that were endangered by the appearance of the Franks and the Latins. Michael had to find any possible way to maintain the independence of his state.

Bibliography

Kordatos G. History of Greece. Vol. VIII. Athens: 20th Century, n.d. (in Greek)

Nicol, D.M. The Despotate of Epiros. Oxford Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1957.

Ziagos, N. G. Feudal Epirus and the Despotate of Greece. Athens: n.p., 1974. (in Greek)

Back to Cover

Back to Cover

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page